Sara Rossberg is a British portraitist who flourished during the 1990’s though she has done later work through the present, and now works primarily with color and texture to distort the faces of people. His most accomplished work is included in London’s National Gallery. Entitled “Dame Anita Roddick'' and painted in 1995, it is a striking and depth filled presentation of its subject. The woman’s face is framed by her frazzled red hair, her face also with a tint of red. Her lips are thin, as are her eyebrows. Her facial expression is intense and soulful, livened by her anxiety or mournfulness, particularly (and inevitably) projected in her pained eyes. A nice touch is that Dame Anita’s blouse peters off into being of no consequence while her hair had very much caught the face that would come below it. So Rossberg provides an internal soul made very visible, when Sargent, the master portraitist of a century ago, has the audience draw out of their regal and polished presentations each of their fully human and individual consciousnesses. The Rossberg painting shows people not disassembled but in their inner thoughts, looking composed in their everyday lives and yet still penetrating. A worthy addition to the collection.

I prefer, however, a not much earlier period of Rossberg’ work. It took place in the Eighties, and I think of it as her attempt to try to find something to do with art, to find a new style or gimmick, that would fill the art scene that had postdated Abstract Expressionism, new resources still needed for painting to fill the void of Rothko and the rest, even at Rossberg’s thirty year remove from that movement. Abstract Impressionism had been replaced in the Sixties by Op Art, which used optical illusions so as to confuse and disorient visual art, and also by Photorealism, also a style of the Sixties, where there was an attempt to replicate a scene, such as the area around Grand Central Station, so as to be as close to possible to a photograph, as if to beg the question of whether to bother doing so if photographs could be done instead, perhaps just for the hell of doing something difficult, and so a gimmick rather than a new insight into the visual, this a practice of what would become the highly conventionalized contemporary art that followed, filled with animated figures of sports teams, just to show that it could be done.

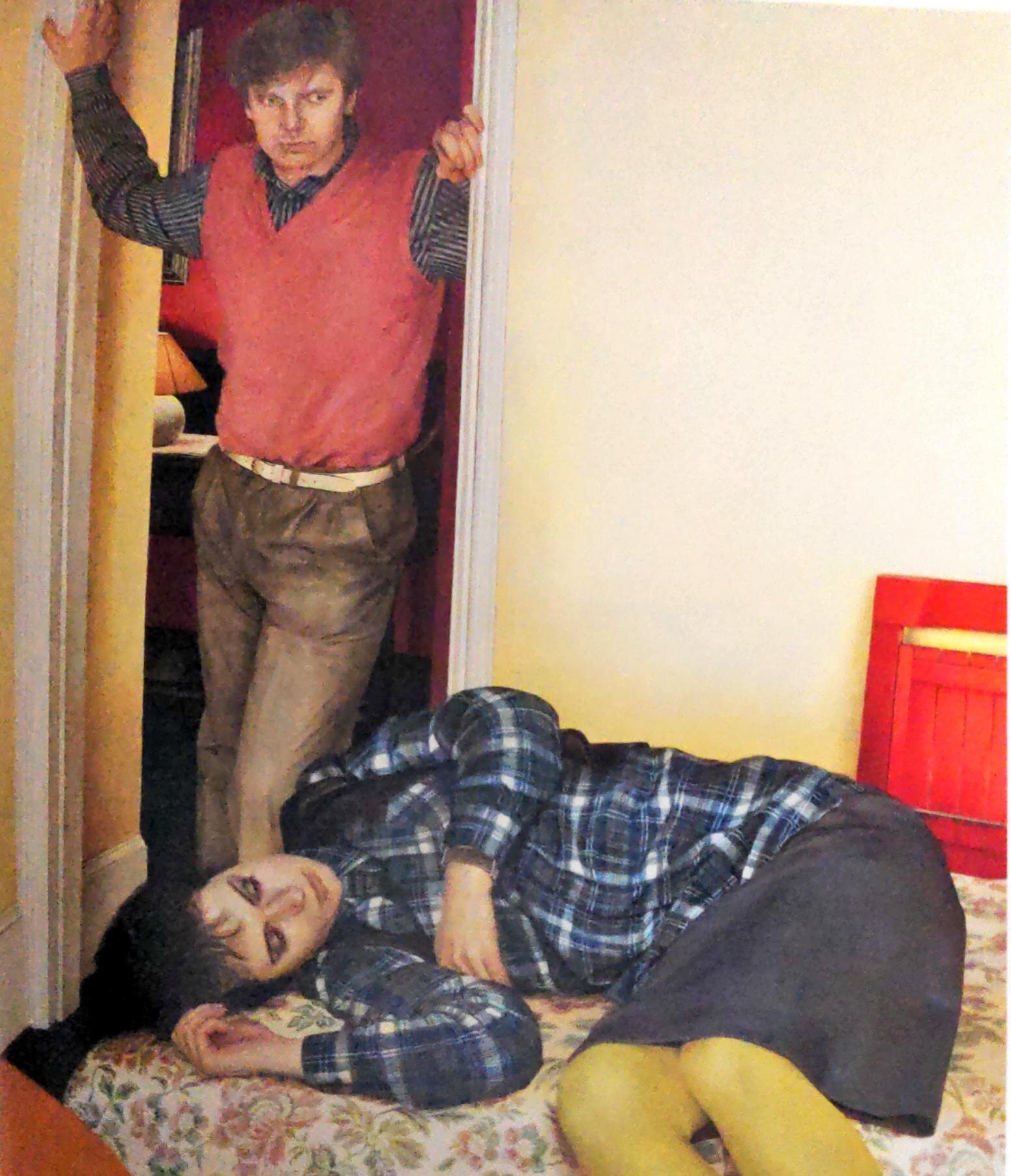

Rossberg was different in that she posed her group portraits so as to restore representationalism but with an eerie look that made it very contemporary however much she was using and commenting on art history so as to accomplish something different as an experience that was beyond portraiture, Rossberg engaged in story paintings, something done by Vermeer, for one, but her paintings would be distinctive in they would capture a feeling of a moment so as to reach back to what created the moment and what might unfold later on, after the moment. One of the two paintings included,in “Two Sides”, from 1985, shows clearly what she is up to. This is a joint portrait but not a pas de deux in that the man standing up who is looking at a reclining girl who is either asleep, or dozing, or about to be awakened, is an adjunct figure who places the setting for the reclining girl, who is clearly the main figure. Why this moment? It makes sense because he is presumed to be a boyfriend who sees her in repose, rather than a reclining woman seen by the portraitist who is imagining or posing the woman as an object of contemplation. The boy friend or maybe even a brother are tied to one another in that they are casually dressed, he in baggy pants and a nondescript sweater and shirt, while the female figure is also informally dressed in a flannel shirt and a nondescript skirt, but does show her stockings to be of an unusual shade,that indicating that she is fully female even in such homey surroundings, her legs modestly closed even when she is dozing or sleeping. Her face is relaxed and is pretty or companionable even if asleep, and yet there is no sense that she is motivated by anything except hat she is exhibiting herself, which is inevitable, while the man looks down at her, and so he is paying attention, even if we do not know what he is thinking about, if anything.

So this is a moment of no great moment, people just being with one another and their own silences, though that without the weight of silence we find in Hopper. It is just quiet and nothing much to report unless the man is indeed about to wake her up rather than move on to the next room. Amd yet, characteristically in Rossberg, the moment seems tense, perhaps because it evokes the experience of something about the momentary that is so allusive that the artist can indicate but not capture any more than what it is to reveal something about the momentary. Perhaps that moment is captured because of the postures of the people: the man touching the door of the room with his arms, the girl looking a bit contorted, as often does happen with people who are dozing, one arm across her body on her side even as her lower torso and her legs are at a different angle, just about hanging off of the bed.The flannel shirt is baggy and its detail offers itself, just as would be the case with a very ample and multi folded dress that a portraitist might capture in an earlier age.

So it is only after the setting, the duo, their postures, that the portrait viewer comes to consider the face of the woman in the portrait. She is appealing but not either particularly pretty or interesting. Her face is rounded so as to make it a bit plump; her eyebrows are well sculpted and her closed eyes show pinkish lids; her lips are ordinary. All make her neither a model or an excess. So the focus goes back to the man? What does he see in her? Is it the mystery that exists in any female? Or is she known as a fully filled human being that goes beyond being female? Oris it that his nature is disclosed only when she wakes up, like any sleeping beauty? We don’t know what the man makes of her and so that is a story painting, because that moment of stasis will move on and reveal to him and perhaps not to her what she is and what she becomes.

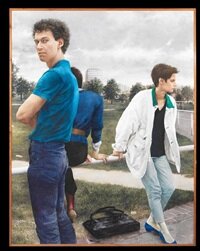

Who are these three hoodlums hanging out together in the group portrait paint by Rossberg in 1986 called “Last Light”? They have similar haircuts, informal and not striking clothes, and scowls on the two of them whose faces can be seen, and a posture that reveals independence and hostility, the most prominent of the three having his arms crossed as if the three of them were looking for trouble. The three are at all angles to one another, yet cramped together, as if three twigs that had overlapped, rectangular spaces just as other group portraits such as Raphael’s “The Virgin and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist'' ,who composed his triple portrait as a triangle, as did many other portrait painters who embraced the principle of having triangles spaced around and overlapping one another. (The shift from triangles to oblongs seems a weighty matter, but leave it to another time.)

The scene in “Last Light” seems claustrophobic, as is the case in many of Rossberg’s group portraits of that period, even though the three seem to be on a football field because there are white stripes, most of the view occluded. Maybe they are teenagers or maybe older than that but still using the facilities they no longer occupy as their present place, wondering what to do with themselves now that they are grown. The three hang together but there is also a sense of mutual rejection in that they do not look at one another, but instead have private feelings that they share. Is it anger, anxiety or what? The viewer thinks of what will unfold. Maybe the dominant of the three will find an occupation or one of the others will remain in gangland or some other unsavory work or just get over their pretended insouciance and swagger. They are a roadshow for “West Side Story '' without the DA haircuts, their postures of stridency cultivated by the Jerome Robbins choreography: straight and pointed, bristling.

Then the viewer comes to concentrate on the most slender of the three, having dealt with the eyes and posture of the stare of the figure who has been most revealing. The scowl is the same, the clothing nondescript and similar. But that figure has thin socks or stockings and trapeze slippers rather than shoes or sneakers or boots. So this is a hoodlumette rather than a hoodlum, and so a different story emerges of what will become of her. Maybe she is a tomboy who has been caught up in male culture, and maybe she will grow up to be a woman who does not need these churlish ways, or maybe she will remain permanently damaged by having associated with the two men. Her trajectory is alike and different from that of the male course, however similar may be their gestures at the moment when it presently exists. Possibility and change are what make this a story picture rather than just a strange triple portrait, just as the older religious arrangements of a single triangle or multiple triangles showed what had gone before and what will go after the placement of a Holy Family.

The most complex, I think, of Rossberg’s duos and trios is “Radio Times”, from 1987. There are three people here sitting in a cramped room. The lefthand most figure is a young man dressed in his Rossberg usual nondescript clothing, so as to convey casualness and the way people really do dress when they do not dress up. He is wearing a bathrobe over a shirt open enough to see his undershirt and so I infer that he is feeling cold. Rossberg is very careful about male clothing in that they are not used to convey the dandy but show a way of being, the male way of being, that is usually used in describing the way women dress. He is seated in a chair and behind him is a television screen with script on the screen, which suggests that this is an early computer because there would not ordinarily be printed lines of words in a broadcast television setting. Supporting that idea is that beneath the television set is a file cabinet of numerous small cubicles which were used, at the time, for discs or other computer type paraphernalia.

The young man may have been interrupted in his work because he is looking back, his neck outstretched, to the dog who is held in a towel by another young man, perhaps because the second man has just been watched by the first as the dog is also being cold. That second young man is just passing through the ordinary activities of a household, while the third figure, an elderly lady who perhaps fills out their household with his two sons, looks distracted, maybe because she is an old lady, or because she has a sense of his household without it requiring her to pay close attention. The visual cues that allow the reader to infer the story of someone at home doing something new and maybe important is also elaborated by the contrast the picture shows between the animated and contorted computer operator with the relatively passive cuddling of a dog by the other young man and the third way of being, that of the taciturn elderly woman. Each of the three figures have levels of activity, ever more animated and important as we move to the left of the frame. So the significance of the event is only in part that momentous things might be occurring during the ordinary, which is worth thinking about, but because the picture shows three kinds of being: particularly active, ordinarily active and passive, which is what can also be described by painters as their poses of the Christian family, with Martha and Mary and the descending Jesus. We each are the kinds of ways we act. Rossberg is being very philosophical.

Rossberg does something more than bring up to date her classical shapes and tropes. She makes something new about how eerie and ominous is the world she has created, partly because of his contorted peoples, as if they are being forced to live in the frames, or because of their expressionlessness that conveys meaning by inference rather than by people announcing so in their dress and their activities, as when we know what the syndics are saying to Rembrandt even if his subjects remain silent. They are, in Rembrandt, what they appear to be, while Rossberg is full of potential, of unrealized beings. So I think what she was doing, at least for a while, was organizing to be a new form of art rather than just another example of a style of art. It was a new form in that visual gesture and arrangement were subordinated to its narrative purpose, full of the surmises that are familiar in literary art, full of both filling the past with its might have beens and the present with its intentions, what might become. Rossberg’s were a painting about literature, and so very different from the op art that was trying to be as spectacular as Abstract Impressionism and as purely as difficult as painting practice, as in Photorealism, however much Abstract Impressionism had been so creative in using minimal techniques, such as the absence of figures, so as to create its emotional impressions. But Rossberg, as is an artist’s wont, did what she decided to do, even if I am sorry that she gave up the endeavor that I so value.