Cultural mutation is a way to understand what is happening in a number of politically charged issues from race relations to foreign policy even though social scientists do not usually treat culture as something subject to spontaneous or creative change. Culture is usually regarded by anthropologists as the continuing way of life of a people, embracing customs, laws and beliefs, and so very stable and self-perpetuating and arising for unknown reasons, while sociologists emphasize the way culture reinforces the social structure that exists because it is transmitted by institutions that are answerable to the structure, as when television transmits what its advertisers will approve of, social media a maverick in that there opinions percolate up from the people, and there is an understandable reaction by which government and other institutions of culture, such as the press, want to see the social media controlled so that they do not promulgate unpopular opinions. Culture is also taken to be a bridge or the medium through which change takes place in that culture diffuses innovations across a population, as when it spreads knowledge of vaccination, even though it is not responsible for original ideas. These theories are contrary to the perspective of humanists, which sees culture as the source of new ideas, whether in science, as when Darwin and Newton invent new perspectives because of their own ruminations while building on precedent thinkers, Darwin a mutation on Malthus and Lyell, while Newton was contemplating Copernicus and Galileo-- and vaccination was, after all, invented by a particular doctor in England on the basis of his observation of cows and the lack of smallpox among cow maids. Ingenuity and insight count. The humanist perspective can be applied to current events.

Read More3/23- Noah and God

The redactors of “Genesis” were concerned with the development of technology, something that is immediately experienced, pervasive, and stands out from the natural world as a human artifact that confounds otherwise ordinary senses of scale and distance. That is true of even the creation fable that leads off “Genesis”. The creation fable does not offer creation done instantly by a powerful god nor does it relate a story of conflicts between gods that would motivate a god to create the world. Rather, as was suggested previously, it offers the set of processes that have to be performed in a particular sequence whereby the natural world, as humankind would know it, might become established. What is more fundamental comes earlier in the sequence. The separation between night and day had to proceed the separation of the water from the land and that had to proceed before the animals could be created. God stepped back after each day’s labor to note his accomplishment. So He made the heavens and the earth rather than simply called them into being. Joseph, at the other end of “Genesis”, offers the social technology whereby the results of a famine can be avoided. That, on a more mundane level, is also a story of how to get from here to there, the creation of an agricultural surplus a process and not simply an intrusion.

Read MoreCampaign Rhetoric

The conventional wisdom is that political parties try to correct the mistakes they have made the last time or two around. So the Democrats didn’t want to nominate another clearly Liberal and Northern candidate after Mondale and Dukakis were defeated and so turned to Bill Clinton, a Southern Centrist who might pick up some of the states that had gone to Jimmy Carter, who was from Georgia. And so the Republicans, in 2020, will alter their primary structure so as not to let the nomination go to a crazy, by then having been saved by Robert Mueller from having to renominate Trump. Democrats, for their part, are going to look for a candidate with a little more personal oomph than they got from Hillary Clinton, who they blame for having lost the race, though we still do not know whether that was the result of of Comey or Russian interference. Remember that her margin over Trump went up after each of the three presidential debates. Those who tuned in knew who was and who wasn’t Presidential.

Read MoreThe Limitations of Painting

One of the things that made Sargent a great painter was that he appreciated the limitations of painting. At least for two hundred years before he did his work, painting had not carried philosophical messages or meanings encoded in symbols but rather did what it was capable of doing, which is to show what things look like. Sargent has no symbolism, no iconography, only what people, particularly, look like in their faces and in how they dress and in their presentation. What Sargent gets from accepting that limitation is an attention to detail that allows him to pick up the telling detail that gives a picture drama even if not anything that could be called meaning.

Read More2/23- Adam and Eve

The creation of woman should not be seen as an afterthought by a God who had previously provided each of his animals with a mate but overlooked doing it for Adam. God may have thought that Adam was a special enough creation, meant to rule over the rest of it, and so he did not need a mate. But either God changed his mind about that or always knew that he would make a special creation later. Woman was a special creation so as to emphasize that in the actual world the relation between man and woman is not like it is with the pairings of the other animals; some special kind of creation was required. Eve was as close to Adam as his own rib. As a legend might, the story of Eve’s creation suggests that woman has thereafter an ambiguous relation to man: part of him, descended from him, and yet a companion to him, and so clearly something different from what happens with some other created species no matter how much it might occur to a son of Adam or a daughter of Eve that the two sexes had different natures. We can see this more clearly if we consider the type of literary undertaking the story of the Garden of Eden is.

Read More1/23- The Creation Fable

This is the first of a twenty-three part series on the Bible. The general theme is that the Bible is for the most part in the vanguard of those who want to secularize history. That means that the authors of the Old Testament, and even of the New, are interested in dispensing with mythology, reducing the number of supernatural interventions in history, and moving the center of religious concern away from magical moments to moral questions.

The creation story in “Genesis” is a far more modern thing than it is usually credited with being It is a kind of philosophical presentation and so very different from mythology which, as Ovid, that great student of mythology, noted, there are always biological transformations of things even while the gods remain subject to the forces of nature and the raging of human passions. Narcissus becomes his image but only symbolically, and not all narcissists become their images, which is what happens in a fable. The creation story is best explained as a fable, which is a story that explain a set of circumstances that do not seem to be created but which somehow were at a point in time and have become part of nature. Tigers have stripes and the Red Man got baked right, neither too much or too little.. Fables suggest that there is a history for what seems natural, a sometimes serious, sometimes fey attempt to make explicable what seems not to need explanation or else to make explicable something which seems paradoxical: how something could come into existence when it already had to be there.

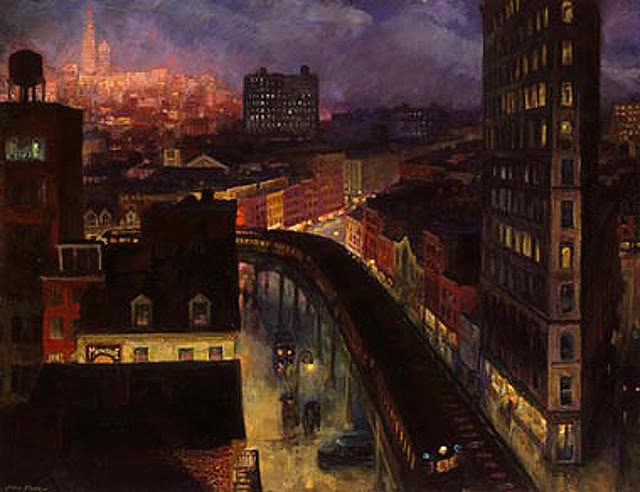

Read MoreJohn Sloan's Distinctive Cityscape

John Sloan’s well known painting “The City From Greenwich Village”, painted in 1922 and now hanging in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D. C., is a prime example of the Ashcan School, called that because it focussed on the grimy realities of city clutter and constant construction and the working class people who lived there. The painting remains striking because it provides a distinctive and very American view on the nature of city life, one quite different from the idea of urban life found in British, French and French presentations of citylife. James Whistler takes London bridges and turns them into swathes of dark color on a dark background to create paintings that are forerunners of Rothko. Cezanne fills the wide boulevards of Paris with crowds of people. Ernst Kirchner and other German Expressionists portray a Berlin crowded with strange looking people enjoying the nightlife. Sloan emphasizes, instead, how important is the physical aspect of cities, both the architectural structures and the architectural infrastructure. Spatial relations are more important than ethnicity or crowd psychology in explaining citylife.

Read MoreThe Upside of the Shutdown

Optimist that I am, let’s look at the upside of the government shutdown. Sure, eight hundred thousand government workers (not all Democrats) are without a paycheck, and there are the additional thousands who are lunch counter operators and dry cleaners who will never be compensated for their lost revenue. But the important point is that the border wall issue is one without content. Republicans fudge the difference between a border wall and border security because only political people think the wall is needed and Trump thinks so only because he became entranced with the term during the campaign. Trump is also the hands down worst deal maker of all time. He could have gotten twenty five billion for his wall last year in exchange for a bill guaranteeing the Dreamers a path to citizenship. He agreed to the deal when it was presented to him by the leading Democrats and Republicans but reneged on it after Stephen Miller got his ear and suggested the deal also include changes in general immigration laws so as to bar what they call chain immigration, which means uniting families, such as, for example, Melania’s family, brought over under those terms to the United States, as well as getting rid of a lottery for some immigrants. Miller also wants to cut the number of legal immigrants allowed into the United States. So we are left with Trump now shutting down the government to get a fraction of what he could have gotten if he had really thought the border wall were a policy issue, which he now claims, rather than a campaign slogan.

Read More9/9: Jane Austen's Critique of Kant

Lest the message of what might have been is lost on the reader of “Mansfield Park”, Jane Austen steps forward as she opens the novel’s last chapter to give in a form even more terse than the rapid fire narrative of the events of the prior few months the denouement of her story. Far from drawing a moral message of how everything is resolved for better or worse, how people pair off as nature intended, with Fanny getting the Edmund she rightfully deserves, she shows that Fanny gets Edmund because that is all that she deserves, in the sense of a person who she is prepared to deal with and who is prepared to deal with her on the terms of the claustrophobic life of Mansfield Park now doubly enclosed by the moral Methodism which Mary quite properly characterizes as Edmund’s. It is not just that both Edmund and Fanny were quite right in thinking that they could not bear the constant sensations of dealing with the candor and overt feeling of their previously intendeds. It is also that they have each been more true, all along, to their own feelings of self respect which they see mirrored in one another than they have in the interests of the family at all.

To the reader’s surprise, there is no recrimination by the family for the role Fanny played, largely through inaction, in bringing about the scandal in the family. To the contrary, she seems all the more indispensable to Mrs. Bertram, and seems to Sir Thomas Bertram to have been morally correct in her reading of Henry, though she has her own silent misgivings about whether or not she would have not eventually accepted him if he had not been so foolish as to fall again, at least temporarily, for his prior love. Mary was quite right in thinking that a little encouragement by Fanny might well have saved him from following his impulses. Moreover, the family, in its morally diminished state, with Maria dishonored and Julia badly married, turns to Fanny as a reminder of what they themselves once were, an icon of country respectability, which she has become more than they ever were. And so her eventual marriage to Edmund, which had been unthinkable because of her rank, and because she was sisterly to him, becomes thinkable as the emphasis is placed on her as a distant relative who has risen in manners well enough to give substance to the feeling that the family is respectable once again, though she brings nothing else to the marriage.

Mrs. Norris, who had always served as the family Cassandra, reminding them at the very beginning that this is the way things might turn out, finds herself the subject of Sir Thomas’s disapproval, perhaps because she is a reminder of the extent to which the little girl who was taken out of charity to serve as a high level companion to his wife, has become the dominant figure in the family, replaced his own daughters in his favor, which seems particularly unnatural and uncalled for. Mrs. Norris, knowing that her place is no longer welcome, since in the key test of the Rushfords and the Crawfords she had seemed to judge badly, has little choice but to acknowledge her failure and move out, leaving the field not to Fanny who has after all moved far beyond her and replaced Lady Bertram as the leading woman in the family, but to Sally, Fanny’s younger sister, who has now become the main companion to Lady Bertram. That defeat by two sisters must have been too much, though as usual Jane Austen does not describe the emotions that have overcome her at the prospect of Sally, but she does describe the statements Mrs. Norris makes about the inconsiderateness of the family to Maria, and those seem just. Mrs Norris goes off to live with Maria as two ladies alone, which is no great sacrifice to Mrs Norris, who gains a companion and who can live in a style appropriate to someone who has rage against an unjust world, just as Fanny would have lived with William, her brother, if the concatenation of circumstances had not worked out in her favor.

Mrs. Norris is thought badly for her candor in saying what Fanny had thought, which is that her acceptance of Henry Crawford would have averted the family scandal. The family is in no position to consider such possibilities, but in the tradition of Humean morality, feels such sentiments as its position now entitles it to, which is to think well of Fanny. This fact finally secures Fanny's position, since it is no longer a matter of mere sentiment, of charity un-buttressed by self-interest.

Sir Thomas has no good explanation to give for the series of family disasters. He turns to the usual set of banalities that are trotted out by parents and experts whenever children of any social class go bad. He says he was too permissive with daughters who had been flattered by Mrs. Norris, as if she had raised them, but who is now the repository of all blame. Fanny had turned out well because of her adversity. This is so lame as to be comic, since Fanny's mistreatment by Mrs. Norris had not bothered him so much before then that he had put a general stop to it, however benevolent he was in lightening her disapproval of Fanny by granting individual acts of mercy and graciousness. Who would have needed the mercy of this beneficent God if God had not established a cruel world to begin with? The reader is also aware that the benefit of Mrs. Norris’ attentions had driven Fanny even more deeply into herself, made her a more clever version of Mrs. Norris, who knew better than to speak out of turn, and accounted in part for her inability to respond to Mr. Crawford, because she did not feel she could possibly deserve such attentions, given her condition and defects, all of which had been made abundantly clear by Mrs. Norris.

So Lionel Trilling is correct to say that the ending of “Mansfield Park” does not leave us feeling good, even though it ends with the conventional marriage of erstwhile hero and heroine and their entering into the life they desired. The ending is not satisfying, however, not because our hero and heroine are such smug creatures, but because the novel never lets the reader forget that any number of other possible endings might have taken place, and that this particular ending is not so perfect, for it represents the fact that Fanny and Edmund are limited in their prospects, settled for what was comfortable rather than what might have challenged their souls. This is less upsetting in the case of Edmund, who was never very perceptive, once he got interested in women, and who seems to have the character of a clergyman, which he was gracious enough to accept without complaining, once he had no choice but to become one, just as Fanny has once silently accepted the fact that she would probably never consummate her love for Edmund. It is more unsettling when applied to Fanny, who after all had potential, had made herself into a creature of the gentry class, but could never force herself to brave it into London or polished society.

Fanny had done more than she could have been expected to do. She was a girl who was clever and deferential, who turned her reading and her brain into a way of moving up significantly in social class partly because she had no choice but to succeed or fail, to live up to the correct manners required of her since the day she arrived at Mansfield Park or else risk being shipped back if she should lose favor. She had to make the manners part of herself more than the others did because she was so dependant upon them, and so they took over her being in a particularly remorseless way, which made her constitutionally incapable of taking on the next leap and transforming her personality into one that could have managed the moral life of the London set, though there is no reason to think it any way worse than that of the men in the country set, who simply disappear for long periods to go hunting, drinking and wenching at a distance rather than close to home. It is, moreover, understandable that having partially gained acceptance at Mansfield Park, though by no means secured it, she would not want to take a risk with her new found selfhood to remake herself yet another time. She was too old for that. Jane Austen's protagonist is therefore only heroic to an extent, to the point absolutely required by her condition, and since her condition is so precarious, and has been so for so long, she cannot be expected to drain herself of her remaining psychological resources by daring again to remake herself. That would be foolhardy, even if the reader would like to believe his heroine could go on forever outwitting the world and conquering ever upwards. Trilling finds society oppressive because it isn't pure possibility, but has some resilience of its own, giving under concentrated pressure but not always yielding. Jane Austen, to the contrary, seems to think Fanny's achievement remarkable enough without requiring her to toss it all away to become someone who might not be able to cope with a husband’s philandering.

An even more deflating residue of the novel, however, is its depiction of the nature of moral life as that is successively redefined by the novel. Morality as generalized principle comes to replace a calculus of self interest. The last chapter of the novel suggests that generalized principle is not enough because the world gets turned so topsy turvy that it is not clear whether a generalized principle is a good enough guide to self interest. At the end, it seems that Fanny has been good because she has been Kantian. She has embraced principle for its own sake. She acts correctly regardless of consequence, and proves to impress the rest of the world with her moral rectitude. Morality is her power and her strength.

But this is a very flawed version of Kant. Fanny’s is still what Kant would call a prudential morality in that it is adopted for want of any better way to act. A person acts morally only because whatever calculus one makes may not work out. This level of ignorance makes it incumbent to act morally in the first place because if things go wrong then there is the satisfaction, at least, of having acted properly. This is appropriate in a topsy turvy world, but it is not what Kant meant when he said that moral action should be taken for the love of acting morally not for the sake of being known to oneself, much less to others, as a person who acts morally. Fanny may come to learn to be moral as well as to want to be moral, just as Pascal suggests that practice may lead to belief, but she is not there yet, and it is not at all clear that that would be such a good thing. In a prescient critique based on Methodism of what would become elaborated as Kantian ethics, Jane Austen notes the moral deficiency of this moral stance. It involves an inturning of the self, a loneliness which no communication can breech, for only in the self is it known whether an action was taken for the right reasons. Kant may want to turn humankind into a set of moral monads, each person operating as if they were totally independent in the world, and only fortuitously conjoining their actions, or doing so on the basis of high seriousness, rather than on the basis of the give and take of life, but Austen sees this as a sacrifice which Edmund, but more especially Fanny, makes. Fanny's strongest moral trait is her reticence, her unwillingness to speak what is unbecoming even to herself, and that means that her life is necessarily filled with unvoiced defeats and even tragedies and even successes. She cannot gloat, but neither can she savor; she cannot whine and browbeat, but neither can she express or seek the need for compassion. This removal from human life has made her triumphant, but more largely speaking, it is what she is.

In short, the critique of Kantian morality is that it removes people from people, supplies them with only, perhaps, their own heart to consult, and even that at considerable risk. Kantianism is thence not a triumph of reason but a retreat into the Romanticism that is on the rise in the world: a paean to emotion that comes from the fact that people have become self-enclosed and therefore preoccupied with self rather than because they have been liberated into new kinds of experience. Jane Austen, who lives on the cusp between Classicism and Romanticism, is not unmindful of the kind of liberation Romanticism supplies. After all, her own self is turned to the energies of art and the position of the observer, but she does not contemplate, here at least, the position of the heroic poet who acts, the Byronic figure, but considers instead, how much is given up by looking at the multifaceted self and not at the multifaceted social reality it reflects, for that is to take a self out of the action, out of an engagement with life, and means betraying the self. Fanny's final tragedy has nothing to do with whether she marries Edmund or not. It has to do with the creation of a self other than the Classical one, and the ambiguities that are resident in such a self.

What accounts for Fanny's rise in the world from a poor relation to the new daughter in the family who will soon be courted by a highly eligible bachelor, and whom Sir Thomas has come to treat as his own daughter, and whom he likes and respects more than his own daughters? The suspense of the novel is that Fanny seems sooner or later to be headed for a fall, either through circumstances, which would make it unfortunate, through the venality of others, which would make it melodramatic, or through her own character, which would make it tragic.

All of these possibilities are available. Fanny is both headstrong and remote, and so could miss an opportunity available to her, or blurt out the well merited grievances she has piled up against the family, and suffer the consequences of being ungrateful to those who think there is no end to the gratitude she should feel towards them. She might not be able to withstand the onslaughts of Mrs. Norris, who would do anything to turn something Fanny does against her, whether it were deserved or not; or Lady Bertram, who is so suggestible and weak that someone could turn her against Fanny, or might manage to do so herself if for some reason she took it in her head that Fanny had been insufficiently attentive; or the sisters, who have no great use for Fanny if she should become of sufficient importance to be noticed by them as something other than a dependant.

External events rather than family intrigue could also lead to Fanny's downfall. A turn in the family's fortunes, or a rearrangement of the family so that Lady Bertram would have to, let us say, take on Mrs. Norris as a permanent lady in waiting, or the need to pack off Fanny to serve that role for one of the sisters, would also lead to a reduction of Fanny from her recently elevated position to her "permanent" rank as a poor dependant. In any of those circumstances, Fanny might be turned against herself, reinterpreted herself as ungrateful, and so no longer secure in her insecure position.

None of these disasters come to pass even though the reader has been waiting patiently and deliciously for Jane Austen to invent a particularly clever and unexpected way for Fanny to fall, the novel serving as a kind of mystery story which provides clues but not the conclusion not to who done it but to how Fanny was done in. So the reader begins halfway through the novel to reread it for the reasons Fanny leads such a charmed life.

Fanny works her way into the good graces of the family because, first of all, they are not so grand as they make out. Sir Thomas had married considerably beneath him, for sentiment rather than good sense. He has a wife who needs constant attendance and is not much good for anything. But for her brief conquest, she might well have fared no better than her sister in Portsmouth who also married for love, but to less advantage. The work of Mr. Bertram’s' life seems to be to try to raise the sights of his wife and her relatives, to reach below him and provide civility to his inferior relatives, perhaps because that is the best such a soft hearted gentleman can be expected to do. In that case, Fanny appeals to him as another case to work on, and of considerably better capacity than the other materials he has tried to form, and so not so out of keeping with the rest of his life, either what he is doing now, or what he chose to do years before-- though it is to his credit that he does not harbor bitterness about past decisions.

Fanny is herself up to the task of being remade because she is more master of language than anyone else at Mansfield Park. She says things in the way they should be said or does not say them at all. She is not given to the gaffes of the rest, and so it is no wonder that Mary Crawford picks her out for friendship as one who can be talked to as a sister. Fanny is tongue-tied when she is called upon by Henry to say something to him, because nothing that she could say would tie together her feelings and her situation, but no one else in the family could have spoken with such candor to Mary, telling her that her brother was not to be trusted because he was a flirt, declaring her real motives in a morally appropriate manner, and so earn from Mary a laugh and a remark that acknowledge the truth of what she has said.

For this and other reasons, Mary takes Fanny to be the sort of person who could indeed rise up not only to the social class of the minor country gentry, but to the stature of the more worldly London families, who have their connections in the Admiralty and the other institutions that control English life, which is all the more reason why Mary is confused that Fanny would not take the opportunity to marry her brother, but seems instead to prefer the morality of country respectability, to which she and her brother have condescended with a liberality at once real and affected, as was the case with many Eighteenth Century city people who have nostalgia for what they see as an antiquated and disappearing but charming manner of life. Such a life is attractive to the Crawfords because it is a non-threatening alternative to their own insecure positions as the Fanny like relatives of a more distinguished family patron. They do not know that Fanny is shocked rather than sympathetic to their own view of the servility imposed upon distant relatives by the heads of families. They do not know that she is self-limiting and that therefore her failure to move up in society as far as she might could be considered tragic, our third possibility for explaining her fate, when it is, instead, settling for what she wants, and so not tragic at all, Jane Austen, among her other accomplishments in this novel, supplying an answer to the idea, which will become everywhere obvious in the Nineteenth and the Twentieth Century, that you are only satisfied if you go as high as you can. Jane Austen turns that wisdom on its head by declaring that people go only as far as they want to, and there are no end of sociological studies which justify the idea by showing that people do not go so much from the bottom to the top of the social ladder as move up one or two rungs in the course of their lives. Jane Austen explains why.

The Double Action of Stories

What makes a story a story rather than just a sequence of sentences is that all stories engage in a double action. Every sentence in a story, even a description of the weather that provides the atmosphere surrounding its action, does two things: it tells the reader of something that hadn’t happened before and at the same time provides information to the reader about how to understand what is to later unfold or has previously occurred. You learn of Macbeth’s forebodings of a promising future, which is an event in the play, and you are forewarned about how to greet further developments. The reader or viewer’s mind is provoked to cast ahead because each event is a revelation as well as something that just happened. That is why stories are so magical. They violate the strictures of time by allowing those who hear it to cast back and forth in the story as if the audience were a god.

Read More8/9: Fanny Price at Portsmouth

Portsmouth Harbour

Fanny Price is diffident about life at Portsmouth once she returns there. Jane Austen uses the occasion to reveal the nature of the character that had not been so completely revealed beforehand, perhaps because it would have been too unappealing to stay with, but now that the reader is so much invested in Fanny Price, Jane Austen can show just how singular that character is as well as how Fanny is, like most people, both possessed of insight and limited in her sense of what she wants her life to be like and how she is with other people.

Fanny finds her home at Portsmouth physically uncomfortable, and yet also recognizes the ways in which her family is like the family at Mansfield Park even if lacking their social graces. That recognition forces the reader of the novel to appreciate that morality is an individual characteristic and not just a social one, even if social graces are collectively a morality as well as an improved form of life because those graces do in fact make people more considerate of one another even if her mother is not particularly considerate. Her mother thinks that Mrs. Bertram must worry over the servant problem because that is her own problem of household management, while the truth of the matter is that Mrs. Bertram doesn't worry about the servants at all, because the servants do a better job on their own, since they are better selected and better paid, and because others in the family worry about them. Having servants is not a key to respectability at Mansfield Park. The family that owns it takes that for granted so that they can worry about other things that will establish themselves as of the sort of people they think they should be. But, on a personal level, Mrs. Bertram is not that much better than Fanny's mother. She may be kinder, but that is because she has time to be kinder, and her kindness means allowing Fanny to serve as a high level serving maid in recompense for her keep, as an expression of her gratitude. Mrs. Bertram is, if anything, more indolent than Mrs. Price, and is allowed to be so by her more comfortable social arrangements

But all of this Fanny could take in. What Fanny does not notice about herself is her indifference to her own family, which Jane Austen presents as the family's indifference to her. It is true that they do not present a very lavish table for her when she arrives, but then they have worked harder at doing something for her arrival than the Bertrams did for her when she arrived at Mansfield Park. And she expects them to treat her as a lady from Mansfield Park. But instead, her father settles in with his borrowed newspaper after the family has been more preoccupied with the concerns of William’s life than with what has happened in her’s, which is not surprising since he, after all, had been living with them, and his prompt arrival at his ship is something of an emergency. There is also the sense, however, that Fanny was always like this, that as a child she had also been aloof and removed, that she had occupied herself with her reading and separating herself from the rest of the family by going off to her little room in the same way she went off to her bigger room in Mansfield Park.

Susan, her sister, is the only person in the family in whom she takes an interest. She regales her with stories of Mansfield Park, recreating as best she can the world she inhabited in Mansfield Park, in her imagination, and living as she had when she was there. It is no wonder that the family seems to have little use for her as she lords it over them with her better ways. More important is that she has little feeling for them, makes little attempt to engage them or to appreciate them on their own level. She may reject Crawford and settle down with William in a brother and sister cottage, but she has no intention of either returning to Portsmouth as a way of life, or for that matter engaging in the London life of Henry Crawford, even if she is tempted to do so. Her success to this point has been created out of her firmness, apparent docility, and her ability to be alone and reserved, to gain life from her books and her general principles, and that is the way she intends to be.

That explains her response to Tom Bertram’s illness. She does not know whether to take an active role and request to be sent for so that she can return to Mansfield Park and comfort the family in its time of need. That would seem to be in her self interest as well as an expression of any feeling she has for the family. But she is remarkably reserved, and simply awaits news of what to do, appearing to modestly resist any temptation there is to step forward, lest it be construed as presumptuous, when in fact she has no great desire to express her feeling to anyone, nor such great regard for Tom that she feels obliged to his family to act as if she were properly a member of the family.

But since she does not know what would be appropriate in the matter, she terms her decision not to arrange for transportation back to Mansfield Park as allowing Sir Thomas Bertram to decide when he has need for her, as if she were indeed more a servant than a member of the family. This is the same principle she followed in the case of the play production, when she hesitated as long as possible and made no declaration of what should be done other than her own withdrawal from the activities. She did not feel it proper for her to take a role in deciding what to do, which was appropriate given her social circumstances at the time, but that is a cover, the reader can realize at this further state of the story, for her general passivity, her waiting for events to resolve her dilemmas, of both marriage and family obligations.

The idea of principle is therefore double edged. It means at first simply a generalization from experience about what to do under a set of circumstances, but it moves up into being a rule whereby one settles on what to do in circumstances which are ambiguous or unclear by making the empirical generalization serve as a matter of obligation. It appears to be like a moral rule, since it is what one does regardless of information, but it is still a scientific, utilitarian principle, because it is what one does as an application of past practice only because there is no information to clarify the situation. Morals are rules applied to limited information about self interest. This is a rather narrow and nasty understanding of non-utilitarian morality: it is inferior to utilitarian morality because it is merely a bad, rough calculation which will have to do, and yet it appears in the trappings of high moral language. And that is the way Fanny has conducted her entire life: she has used moral language because she has spend so much of her life in unfamiliar or only barely familiar settings that she has had to rely on general principles to give her a compass on how to behave. Categorical morality is the refuge of ignorance rather than the abandonment of self interest.

Tom’s illness seems to provide a way out of Fanny's overall dilemma. It is a deus ex machina which will resolve her problem, although not necessarily in a way she likes. It immediately occurs to the reader that should Tom die, Edmund will inherit Mansfield Park, and so be in a position to marry Mary, since his relative poverty is the only thing that makes Mary hesitate about a love match. That couples relation resolved, Fanny would have even more reason to accept Henry, for it would allow her to continue to live near Edmund, and persevere in the brother sister relationship that is one side of the ambiguous relationship she knows herself to have with Edmund, while having Henry as a perhaps unfaithful and absent and even possibly transformed husband who she could deal with as she pleased, since he would not be the center of her emotional life, unless she wanted to make him so. It would secure her future, allow her to move in any direction she wanted, while her present situation was fraught with danger because any of the options open to her-- continued association with Edmund, or even marriage with him, and the continued courting by Henry or even the good graces of the Bertrams, could be foreclosed by any number of events, including some simple insult she might pay the family inadvertently, since her connection to them is not legal but simply based on the favorable sentiments they have about her. Her situation is precarious, and Edmund's succession to Mansfield Park would move her in one direction.

Nor should such a possible resolution present a surprise to the reader, however unexpected the letter informing Fanny of Tom’s illness might be. The conventions of the Eighteenth Century novel, as well as the realities of Eighteenth Century life, remove characters from the scene through death all the time, or in some other way provide an external resolution, as when Tom Jones is found to be the illegitimate son but rightful heir of Squire Weston's sister.

But Jane Austen has already so well prepared the way for understanding that “Mansfield Park” is not a conventional novel in which all is made right in the world so that life is in accord with its natural scheme of inheritance and the social scale of being, so convinced has the reader become that people make the best they can of bad choices in which each choice has its appealing side, satisfying some self interest, even if no choice is a perfect one without problems, that the prospect of a deus ex machina comes as a disappointment from which one hopes Jane Austen will save us, which she does indeed do, but not before Fanny receives a letter from Mary which she finds proof positive of Mary's cynical and immoral nature because it is so candid about stating what is obvious about the change in Edmund's fortune.

The reader is less prepared to find Mary's letter so incriminating partly because she does no more than state what the reader has already been led to think about the matter. How could anyone deny Mary the right to have such thoughts? She would have been a fool not to see the possibilities, which are, after all, fully in accord with the morality of self interest which had been the hallmark of Mansfield. But Mary is so foolish as to state them, and to state them inelegantly, as a matter of personal greed, rather than as a matter of what the science of morality would dictate as appropriate under changed circumstances. First off, Mary, for all her graces, was not as clever as Fanny, and could hardly be expected to either find the right way to say something or decide to just say nothing at all. And, moreover, Mary had come to treat Fanny as a sister in the prospect of her becoming a sister-in-law, and so could confide in her more candidly than she would to someone else. After all, Fanny was at the moment confiding all sorts of things to Sally, who was her flesh and blood sister, but whom she had not seen for years and years. It may have been crude of Mary to say what she did, but Fanny is an unforgiving soul, especially of a woman who loves the man she loves.

But then another unexpected event enters the picture: the elopement of Maria with Henry. Again, Fanny remains in Portsmouth, passive, waiting for more information in correspondence from others rather than declaring herself or expressing concern or interest. Mary does not have Fanny to confide in, to perform the sisterly function that would be expected of someone else, but a role from which Fanny is exempt because she has for so long been the great stone face that she is expected to be someone on whom moral virtue is projected: what would she think were the right thing to do? Fanny is a kind of moral oracle who operates from afar, just as Sir Thomas had been, though not as well, from Antigua.

Instead, Mary confides in Edmund, who one would think would supply an attentive and sympathetic ear, since this is the woman he wishes to marry. Mary suggests that, proprieties aside, the interest of the combined families is to allow the couple to live together till they decide to marry. This is not an approval of the elopement but the common sense for which those at Mansfield Park are supposedly renowned. It would be far more a disaster for Maria to be disgraced permanently and for Henry to lose his marriage to Maria than for him to make an honest woman of Maria by becoming a reformed rake. If he were, after all, good enough to marry Fanny, then he certainly is good enough to marry Maria, who is now a fallen woman, and has shown poor judgment before.

Edmund greets this heartfelt confidence between a woman and the man who has expressed interest in marrying her by turning on her, by immediately interpreting this declaration of her’s as conclusive proof of her immorality. When he says as such, in no uncertain terms, she is clearly shocked, for she had been on the verge of accepting him, even though Tom's health had improved, and there would have been considerable sacrifice in the match for her. Her response is, quite correctly, to call him morally self-righteous, unwilling to consult normal moral concerns, and so she tells him to leave. When he does so, she hesitates and calls him back, but he is unwilling to return, which is the contempt he shows for a woman who is not only willing to face the fact of his poverty, but also swallow her pride so that she might marry a man she knows will never be candid with her.

The willingness of both Mary and Henry to marry their social inferiors requires explanation. Both of them, the reader has suspected and it now seems confirmed, are in as precarious a position as Fanny. They have been raised in a house not their own on the sufferance of people whose shortcoming they endure not from familial love but out of social necessity. They border themselves with the Grants for periods of long duration, in part out of what they declare is their sentimental attachment to the country, as well as because of their need to find someplace to live where they can be more than they are, and also out of a sincere admiration for what they see as the orderliness of life in Mansfield Park. But they have both been trained so long in their upbringing to a level of morality which is more candid and more acceptant of the vicissitudes of life that it is difficult for them to appreciate just how constricted are the moral concerns of the people at Mansfield, just how inhibited their language is. So while they are thought of as from a better class than those in Mansfield, and are perhaps therefore understandable as more sophisticated, this sophistication is not appreciated by the Mansfieldians when it has to do with anything of great consequence to them, and the Crawfords, for their part, think the good order of Mansfield does not mean that they cannot be candid when candor is required, as it is often enough in life. What seems eccentric about each party to the other becomes seen as essential to them in moments of crisis. This is a gap which is not easily breached.

Fanny had accepted just such condescension from the Mansfieldians. She had accepted that she needed to learn to behave in a different way than she had at Portsmouth, had accepted on faith that the manners of the richer were better than those of the poor, and yet neither she or Edmund would allow themselves to be tutored in the behavior of an even higher social class, but responded with a narrow mindedness that might have been expected of Mrs. Price. She had risen as far as she intended to in her vision of what a proper life amounts to. And so Fanny remains forever the Portsmouth girl who clings to her final prize, Edmund, because that is the only one she wanted. She was not taken in by wealth or manners, only by her own passions.

Sophisticates

I used to think that sophisticated people were like the people who read or wrote for “The New Yorker”. They were insouciant under the worst of circumstances. I thought up a New Yorker cartoon, when I was a teenager, of a cocktail party where there was an atomic explosion in the background and one guest says “I think it's time for another Martini.” That is sophistication: coolness in the face of difficulties either social or existential. I was also impressed at the time by the ads in “The New Yorker”. They exposed me to products and poses I would never see in my working class neighborhood. These people were dressed to the nines and carried themselves as such. .

Read More7/9: Morals in "Mansfield Park"

Critics have gotten “Mansfield Park” wrong because they have read it as an Eighteenth Century novel whose purpose it is to illustrate moral virtue through the use of exemplary cases. “Tom Jones” raises this concern to enormous proportions because Fielding self-consciously invokes the idea of an epic to frame the comic adventures of his hero, which are nonetheless to be taken seriously because they show the working out of a hero's life, whether that is understood as a result of God's providence or coincidence, those adventures taking place in the domestic world of inheritance and marriage arrangements rather than in warfare or other more usual forms of heroism. Critics are constrained to find the moral universe of “Mansfield Park” unsettling because the high seriousness of the moral squabbling seems unrelieved by either irony about the project of making good marriages (though there is plenty enough dramatic and verbal irony throughout the novel) or because the harsh moral righteousness of the heroine, who seems to embody the moral message of the novel, seems to make her excessively loyal to propriety, just as Griselda, the heroine of Chaucer's exemplary tale about obedience, “The Clerk’s Tale”, seems also to carry a good thing too far, even if the reader can profit from her instruction.

Jane Austen might well have been pleased at such readings, for she is certainly doing her own turn on the Eighteenth Century novel, adopting its structure, plot lines, and tone, and does indeed suggest that the life of morality is not the easy one her predecessors portrayed, but rather, in fact, a life so grim that a reader might think to dispense with it entirely and, instead, take off with Mary Crawford on some romantic adventure, even if it came to no good end and had to be paid for the rest of one's life. That would indeed supply an opening to Romanticism, a transition from sentiments externally stimulated to feelings that well up from the consciousness.

Critics, however, in their penchant for telling a new story out of the story that is before them for analysis, the telling of a new story out of a given text, can fall far short of the mark in that the commentator proceeds only by doing violence to the text under consideration in that what is offered is not a new or additional reading of a text but a clearly faulty one, as that can be concluded by consulting the evidence of the text, even if the misreading has been so successful as to crowd out a more faithful reading of the text. Such is the case with Lionel Trilling, who became an influential figure in mid-Twentieth America because he had a powerful vision that informed his criticism. He stated his view most clearly in his essay “Meaning, Morals and the Novel”. A novel, more than other forms of literature, establishes a moral framework for understanding life because all major characters are on a moral quest to establish what they see as the right way of living onto the ongoing flow of history, as that is imagined in all the richness of detail of which the novel is possible. Their individual takes on life, which is what Trilling takes morals to be, somehow different from custom or overt morality, intersect with the forces acting upon the hero or heroine, and the reader observes how these experiments in living will play themselves out. So the novel is a form of instruction that, in the modern world, has become preferable to that which is provided in a church because it is far more subtle. We go from novel to novel ever enriching ourselves about how to act in life. Trilling is carrying on in the tradition of Matthew Arnold, about whom Trilling wrote his first book, someone who also believed that literature had replaced dogma as the way to guide one’s life, though Arnold did not primarily have the novel in mind. Trilling’s was a noble undertaking in that mid century America was in need of a moral compass that would not indulge in quasi-religious platitudes and would instead appeal to the sophisticated secularist who wanted to find the richness of reference and a sense of the complexity of the world that had in previous generations been offered by religion. The liberal West was not without a soul; to the contrary, it cultivated a highly inflected one. And so that is the story Trilling wishes to unfold in any number of novels, Jane Austen’s “Mansfield Park” just one of them.

But Trilling gets “Mansfield Park” wrong in his widely reprinted essay of that title precisely because he is so hard on the hunt for what he wants to find in it, which is a moral quest, when the whole point of Jane Austen is to be on no moral quest at all but to tell the story of lives as they are actually lived, no judgment passed on the characters, only descriptions of what they are as people, some of those more appealing than others. Trilling starts his essay with his usual grace of style, and that allows him to elide from one point to the next as if one point was earned by the previous remark, though that is not at all the case. Trilling says that Fanny Price is very different from Elizabeth Bennet in that Elizabeth is vivacious and energetic and talkative while Fanny is sickly, uncommunicative and rather dour. This is all true enough but that is used to suggest that Fanny is just a different kind of moral heroine than is Elizabeth, that she too has her principles, those involving support for her cousin Edmund to become a clergyman, which Trilling says is a position that Austen associates with Mr. Collins from “Pride and Prejudice” and so something to be looked down on even though, from Fanny’s point of view, it is the right thing to do.

But, as I say, Fanny is not on a moral quest or even just out to improve her chances in the marriage market in that she turned down a very good match to a rich landholder very much impressed by her, he an amiable mate because she could manage him around and also because he is identified as one of those landholders who want to improve their properties, something of which Fanny might take charge as a suitable outlet for her energies. The reader realizes that the one she wants is the one she has always wanted, which is her cousin Edmund, with whom she has been raised as a sister. Sir Thomas Bertram, who is very vigilant about what happens to his children, cannot even admit to himself that Fanny has this incestuous interest and is willing to put everything else aside, even the well being of the family into which she has been adopted, to accomplish that end. Being a clergyman’s wife is therefore a suitable ambition for someone who has always been a loner, who has made her gaucheness into a tool to get her way, whether to get herself a horse, or by her silence answer those relatives who are critical of her for her low beginnings. She bides her time and finds a way to prevail. So Fanny is no moral exemplar, even if of an unusual kind.

The point of the novel is a keen observation of what it means to take in a poor relation, this offered a generation before Jane Eyre, who was a true orphan, found her way into the Rochester household. Such a situation requires the family to cope, in spite of Sir Thomas’s good intentions, with a mean spirited and selfish child who does not identify with the family but with what she can get out of it, however much that allows the author an opportunity, which a good novelist will indulge, to display the pretensions and idiosyncrasies of a family from the inside, which is great fun for the reader, but does not make the protagonist any more of a heroine. So Jane Austen is not a moralist but instead offers a portrait of a human soul, one of the most intriguing in world literature, a woman not tragic in the manner of Anna Karenina or Emma Bovary, but rather true to herself with all that implies about her true character. This novel is therefore not in keeping with what Trilling believes to be the nature of the novel however pleasing it would be to believe that it fits into his grand scheme. Rather, it is onto something even broader, which is to provide a true rendering of human life, never mind the morality.

But Jane Austen, I think, is even more radical than that. She is doing an even grander turn on the Eighteenth Century novel, abandoning its moral message entirely, if morality is understood as a system of what people are obliged to do out of religious or natural principle, and which they can live up to or not, and instead proposes to describe the moral life with utmost clarity and candor, and to make no moral judgments of her own upon it. Her characters are neither symbols or representatives of anything but themselves, but, as they say, are imaginary frogs in real gardens, constrained only by their own sense of things and their sense of the way the world is, working out their fates as best they can, with Jane Austen acting neither as chorus nor moral focus, but only as historian of their travails. This wrenching away from moral certitude while maintaining concern for the reality of moral choice in the quotidian of everyday life, sets the stage for the Nineteenth Century novel, and for what critics have come to call the moral tradition of the novel, even if that hard headed approach is sometimes challenged by escapes into symbolism, imagery, and the other purely literary pleasures of the novel that make it the rival and successor of epic poetry.

Austen is freed to become a student rather than a practitioner of morality not only because her Humean inclinations towards identifying morality with empathy, and so doing without the first of the two, allows her to do so, but because of her appreciation of what the form of the novel can accomplish, how it can rid itself of the superstructure of being a moral exemplary tale, or even an epic one, but simply the record of how some people fare in the world. Characters in novels are like real people in that their motives are always invisible, constructed by an outsider (or the persons themselves) out of the words they use and the emotions they are recognized or recognize themselves to feel. The motive itself is ever allusive, a supposition based on evidence. The more private the motive the less certainty with which anyone, including the person so motivated, can speak of it.

There is no getting around that general point about the nature of moral life. To consider the characters in novels merely fictions, and therefore to have no life outside the page, may seem to undercut a lot of naivete about the complex relation of literature to reality, but it does so at the expense of the imaginative recreation of characters in the minds of readers, who know well enough that they could never have met these particular people in the street, but know equally well that as imaginative creations the characters have a life of their own, which allows us to speculate about their childhoods or what they do after the novel is over, because if we cannot do that, how can they be characters to us, how can we identify with their concerns or the worlds in which they live? It is no more difficult (and probably easier, since we have more information at hand) to speculate about what motivates characters in novels than it is to speculate about what motivates those real people with whom we interact in the actual world, who we presume to have lives when they are out of our sight, whose character we infer from what they do when they are in our sight and what we hear of them doing. Jane Austen makes no greater demands than that in order to gain our appreciation of her characters. She rarely falls into the pose of voicing the point of view of the character that go beyond the evidence already supplied from more indirect observation, and then, it often seems, as a prod to slow readers who need cues or confirmations to reach opinions about her characters that could have been derived without such evidence.

This deliberate limitation of her own artistic resources sets up problems for narration and character portrayal that could have been solved by the novelistic equivalent of the dramatic soliloquy, which is the epistolary form, or else by the contemplative passage, which had already been used by Swift, even if it is given much fuller development in Dickens and his successors. But this limitation, the equivalent of eliminating in prose the rhyme in poetry, allows Jane Austen to do what few other novelists are able to do, but which so many of them strive for: to make her characters either larger or smaller than life, some of both types in the same novel. Characters whose inner lives are revealed are either pathetic, like Mr. Collins, and as they come to be in the stream of consciousness of naturalistic fiction, or heroic, like Elizabeth and Darcy, as they will also be in the dramatic fiction of Dickens and Conrad. But characters about whom we have no more information than is available about real people, act and move and make impressions that are more like those of real people: a bit at a distance, and much left to inference. That is why Jane Austen's characters can seem both spontaneous and determined.

It is also why they can seem both undramatized and ordinary when most art, in its very nature, works against the mundane by making the very act of attending to its characters turn them larger than life, so that the mental world of the reader is filled with Oedipus and Hamlet and the Karamazovs, all of whom make it difficult for the reader not to think that these characters feel more deeply than ordinary mortals do, that real families are pale copies of the Karamazovs, because their own perverse emotions and rages could not possibly be as vivid and are certainly more passing than those of the dramatic characters. Great heroes are, in that way, like movie stars. Because both kinds of characters are larger than life, they are beyond us and so it is quite understandable that they do remarkable things and are caught in remarkable situations and then do remarkable things. Ordinary life is not like that. If there is a moral message in “Mansfield Park” or other of her novels, it is not the question of what are proper morals but, rather, what is the burden of morality on life as a quality of all life, and the answer grows directly from her perception of the nature of novelistic characters, and hence, actual characters: people mean what they say, and are what they seem.

The nature of her undertaking, as it is to be distinguished from an attempt to only produce another turn on the conventions of the novel, is made perfectly clear by the rapid fire sequence of events that follow from Fanny taking leave of Mansfield Park for Portsmouth, confirmed in her inability to choose between Henry Crawford and the desire, barely confessed to herself, to have Edmund or no one. Fanny has been sent to Portsmouth by the benevolent spirit of Sir Thomas so that she might reconsider her irrational refusal to accept Henry Crawford's proposal. Rather than a new adventure, Bertram and Jane Austen have arranged for Fanny to reconsider an old one: how she came to be what she was. What is remarkable about her life in Portsmouth is how little it changes her. She seems to be more willing to consider Henry, since she now expects to hear from him, and is displeased and somewhat alarmed when there is no communication forthcoming, though she has done little enough to encourage him to persist in his interest in her, but the flattery of his relentless pressure might have worked its way at Mansfield Park as well as at Portsmouth-- or maybe not, which is the way it is in real life.

John Singer Sargent's "Gassed"

After having done most of his great portraits, bestowing a distinct life on each of the women who sat for him, Sargent seems to have been looking for something else to do. He travels the world and portrays it in a number of different styles. There are paintings of Italy that seem like finished architectural drawings, the lines clear, the colors muted; there are busy portraits of people sitting in their gardens, a multiplicity of pastel colors presented in somewhat broader brush strokes than Sargent had previously used. But there is one painting that stands out among these lesser Impressionist influenced paintings, and that is “Gassed”, an elegiac tribute to those wounded by gas in World War I. This painting might seem a mere magazine illustration because the drawing of the figures is not exact and because it seems to convey more information than it does artistically inspired emotion, but that would be to underestimate it, as the Imperial War Museum in London apparently does not, exhibiting the painting under glass as a solemn reminder of the Great War. Sargent used his formidable artistic skills to create an iconic representation of that war.

Read More6/9: The Tragedy of Incest

Fanny Price, the anti-heroine of “Mansfield Park”, has character traits that have been helpful in moving her up in the world to the extent to which she has but which work against her rising any further. Such an irony is sufficient for an Eighteenth Century domestic novel. There are, however, more troubling dynamics in her character, which those around her barely perceive, that make Fanny's life into a Shakespearean tragedy, even if it does not lead to her social downfall. Separating Fanny's personal fate from her social success is part of Jane Austen's critique not only of the social novels of her period, which do not go much farther than define a happy ending as the achievement of social success, but also are part of Jane Austen's critique of Shakespeare, who insisted on correlating personal and social tragedy, when the truth of the inviolable and separated self is that the lack of a social tragedy is only incidentally connected, if not irrelevant, to what is happening in the privacy of a soul.

Fanny emerges as the protagonist of a Shakespearean Jacobean tragedy, not because of her rise in society, or its connection to her fall (since there is no fall) but because of her difficulties in accepting the idea of a marriage to Henry Crawford once it has been settled to the satisfaction of everyone but Mrs. Norris, and before the family is itself sent into imbalance by the elopement of Maria and Henry and the subsequent acceptance of Fanny into full membership in the family. At that point, Fanny is no longer the subject of condescension, but a significant personality who is no longer judged or encumbered by her ungainly manners. Her major fault seems to be the minor one of showing too much deference to her prior position, when others believe, for the moment, that she ought to feel more secure than she does.

It is from this elevated position, and the assumption of family responsibilities that supposedly goes along with it, that she had faced the prospect of Henry Crawford as a suitor. Her rejection of the match, which would seem to bring great good to the family as well as herself, since it is the kind of contribution women can be expected to make to the salvation of the family's fortunes, is only explicable to Sir Thomas as a throwback to prior times, when Fanny might have been expected to have the hesitancy appropriate to a less elevated position. Sir Thomas is willing enough to excuse her response, at least this once. But there is something more in her hesitancy, and it stands beyond issues of class and manners.

By any real world standards, Henry is not at all a bad catch. He says enough things to make this clear. He is, first of all, the only one who shows any interest in improving the land. He actually has some contact with those who oversee his estate, and has made something of a study of "improvements", which is a catchword with the modernizing gentry, raised as they are in a land of steam and canals. Henry, moreover, is willing to be guided by Fanny in how he deals with the land under his control, to accept her judgment about the moral way to deal with his dependents. This is not only more than anyone else is willing to do; it is more than could even occupy their imaginations as a possibility.

Henry also has no trouble we know of in accepting Fanny despite her inferior position. At first interested only in flirting with her, he is the first to notice her even for this potential, because that in itself provides a kind of equality with Julia and Maria, who are far more eligible creatures. His lack of condescension to Fanny and her family, which is more than the Bertrams can manage towards her for a very long while, is so important that Jane Austen pauses to enter the mind of Henry, something she rarely does with her characters, to note that he feels deeply satisfied by the opportunity his wealth provides to give William, who is one of Fanny’s brothers, a horse to ride, which he thinks is little enough a rich man can do for someone who is so admirable because he has devoted his life to doing something substantial. This is not only something the others would not do; it is something only Henry would even contemplate doing.

Certainly Henry is a flirt, first with Maria, and then with Fanny. But it is to be said for him that he did not choose to flirt with Julia, the one who had been assigned to him by order of precedence. Henry is a romantic man. He found Maria attractive, and was encouraged enough to believe that she was not only unhappy with her affianced but would consider him in place of Mr. Rushworth. (Dickens is not alone in identifying people through their names. Everyone rushes to identify Mr. Rushworth's worth by his wealth.) Choosing Henry over Rushworth would mean a sacrifice of income to Maria, but the marriage to Rushworth was so clearly sentimentally unsuitable that only a temporary separation from Henry was enough to make Maria angry enough to lose her judgment, and insist she would marry Rushworth, even though her father gives her every leave to get out of the marriage if she would only say she wanted to. But Maria is not capable of knowing that there are occasions when words are real, have consequences for her life as well as the lives of others, or to appreciate that her father had offered her a chance to save herself from the marriage, to find a safe anchorage for her soul elsewhere. In this, Jane Austen follows Shakespeare's idea that the right marriage is a sort of salvation.

Henry turns his attention to Fanny. This is not as dishonorable as the Bertrams, or Fanny especially, take it to be. Henry had come from London society, which has different meanings for flirtations. Not every one of them are meant as courtships. But, as is generic in Shakespearean love matches, what begins in innocence turns serious. The person who had not been expected to become the beloved turns out to become so.

A Shakespearean reversal should not surprise Fanny who has all along wanted her own sisterly relation with Edmund to turn to love. The suspense over whether Fanny will fall from grace in the Bertram household is joined as a plot motif to the suspense over how the relationship between Fanny and Edmund will turn out. How will she deal with her possessiveness when he finally marries someone else, or how can she possibly arrange for him to find her a love interest? Jane Austen makes sure that the reader sympathizes with Fanny's feelings toward Edmund, so why is it so wrong to suppose there might be a different sort of plot that unfolds, with Henry turning from a flirt into a devoted and sincere suitor for Fanny? That ending would be appropriate if “Mansfield Park” were only a novel of upward mobility, but it is less so because “Mansfield Park” is also about how the intensity of feeling can displace an objective evaluation of things, so that Fanny could except a transformed Edmund from her moral scruples, because her heart warms to him, but cannot accept Henry transformed by his love for her, since she does not respond to his presence as he does to her’s.

Henry's proclamations of devotion to Fanny only seem empty hyperbole when looked at from the outside. That his transformation has been earned by the love of a woman is supported by the fact that he takes her good qualities so seriously, not just as virtues the rest of the family can recognize, but as the expressions of a self, and so the basis for romantic love rather than merely respect. Moreover, these qualities are recognized by him as more essential than her obvious deficiencies as a person without social or economic standing who also combines a minimum of personal attractiveness with a somber and frightened character that rejects all opportunities in the name of circumspection. The concern Edmund and others have that she should not over exert herself is not a false concern directed at the weaknesses attributed to all women, but is specific to Fanny, since the other young women in the family are not treated in that way.

Jane Austen has also provided a precedent for Henry's devotion to Fanny that would make it more plausible if the reader were not seduced into Fanny's way of thinking about things. Fanny does not think the persistent devotion of Edmund to Mary makes him unsuitable to marry Mary. Rather, she thinks his persistence likely to pay off, and that Mary will give in to a marriage that she does not deserve. Why is the same not true of Henry, whose persistence does not seem as clouded as Edmund's is to the character of the woman he is courting? Henry does not praise Fanny for virtues she does not believe herself to have, while Edmund is regularly flattering Mary by describing her in terms that Fanny thinks grossly untrue. But this parallelism does not enlighten Fanny about her relation to Henry, or move her to speak to Edmund about Mary's shortcomings, which as a sister she would be called upon to do.

Henry's final lapse from grace is also more ambiguous than the Bertrams notice, though Jane Austen gives the reader reason enough to suspect that the whole thing had gotten out of hand. Henry seems to have tried to be loyal to Fanny despite her continuing lack of encouragement. Austen lets the reader know that Fanny wanted Henry to persist, but how was Henry to know this? It is not surprising that his interest in Maria is rekindled. (Maria is one of Sir Thomas’s daughters, in case you forgot; there are a lot of characters to keep track of in “Mansfield Park”.) Maria seems hardly at all to be living with her husband anymore. At the outset, it seems, the affair between Maria and Henry was supposed to have been discreet, but someone tattled. Fanny, unlike Mary, chooses to see this as a moral melodrama rather than a moral tragedy. For Fanny, social lapses are still more important than matters of character.

That is because Fanny has learned, if anything, that she gets what she wants only through patience, that she is best served when she holds out against temptation. That is what got her through the years at Mansfield Park, that is what got her through the play, and that is what she expects will get her through the present crisis. For what she wants, which she confesses to herself only reluctantly, is Edmund, nothing less. Fanny sees herself as a kind of Romantic heroine because she will never compromise this goal, even if it means that she never married, and even if she takes the secret of her heroism to the grave. Jane Austen repeatedly reminds the reader that Edmund was the preoccupation that allowed Fanny to remain largely unaffected by the glamour and flattery of Henry, and that no one knew this but herself, in spite of everyone at Mansfield Park and elsewhere spending so much of their lives dissecting one another's motives.

The reason that her attachment to Edmund is unnoticed is because it is awfully close to being incestuous. She had lived with him as a sister for so long that everyone had forgotten Mrs. Norris warning that her proximity to the young men of the house might make her a decidedly unsuitable match for one of them. Sir Thomas, who is usually so careful about controlling social arrangements so that only those occasions for flirtation which he thinks are suitable are allowed, proceeds to dismiss these concerns out of a Squire Western liberality. He insists on drawing a strong line of reason between a paranoid view of class relations, which is bad, and the prudence with which powerful social forces need handling, which is good.

Confronted with Fanny's perversity about the offer of marriage from Henry, Sir Thomas for a moment considers that Fanny might be interested in Edmund, but quickly dismisses it as something of which it would be unworthy to speak. This, in sharp contrast to his willingness to speak to Maria of breaking off her own engagement, suggests that he is not concerned about speaking candidly about the advantages and disadvantages of a particular marriage, but that there is something beyond that in speaking of a possible combination of Fanny and Edmund.

And there is indeed something incestuous about the interest of Fanny in Edmund. We have here the reverse of the situation in “Tom Jones”, where Tom did not know that he was flirting with his real mother. Fanny knows that Edmund is not her real brother, but she does not see that her interest in him is inappropriate because he has been like a brother to her. She saw him within the confines of the family and so she had been privy to his confidences, and had counted on his emotional support during family battles. She feels comfortable with him, as she might with a brother.

The problem with courtship at country estates like Mansfield Park is that husbands are selected as a result of a few meetings on formal occasions with those few eligible men who come from elsewhere. These are slim pickings, similar to those of the country gentry in Tolstoy or Chekhov. These men, moreover, seem unpleasant. They are characters out of Rawlinson: garrulous, self-flattering, and given to the usual vices of country gentlemen, such as drinking, horses and, one presumes, women. Edmund seems immune to those diversions. He seems much more comfortable, familiar. And that may well be why there is an incest taboo: to make people choose people who are not already in the household, because otherwise the family itself would be an emotional cauldron that could not contain its de-domesticated passions, and because people will be able to get outside their own family's peculiarities only by finding someone from outside it.

This Fanny seems unable to do, for the good reason that men who talk inelegantly and wildly, as most men do, are indeed unattractive, but also for the bad reason that she is unwilling to risk the emotional comforts of the family she has settled with at Mansfield Park. In more modern terms, Fanny seems to suffer sexual anxiety: she is unable to see herself consummating a relationship with someone so gruff and loudmouthed and healthy as the men to whom she is introduced, and would prefer to settle for an easier relation with either her real brother in a small cottage or else in a real marriage to her adopted brother. Marriage, for Fanny, is a kind of impossible safe haven of the sort she had made for herself at Mansfield Park. Why should she give it up? The country set may be quite willing to refer to sexual sentiments as motives-- characters regularly comment on who is attractive and who is not-- but language and custom do provide excuses for not facing up to the challenge of the deepest emotions, much less those perverse passions which do not speak their name in any society.

Isabella, in “Measure for Measure”, is not able to sacrifice her virginity for her brother because, Shakespeare suggests, this is too much evocative of her real feelings. She is saving herself not for an imaginary lover, but for the specter and thought of her brother, and so sleeping with another for his sake would be an irony that cuts too close and therefore must be rejected. A similar Freudian reading, by which the truthfulness of a juxtaposition calls forth repression, applies to Fanny, who is willing to reject all men because no man can be as good as the brother she has adopted, unless she makes the leap of faith which romance would require and passion would urge.