Fanny Price, the anti-heroine of “Mansfield Park”, has character traits that have been helpful in moving her up in the world to the extent to which she has but which work against her rising any further. Such an irony is sufficient for an Eighteenth Century domestic novel. There are, however, more troubling dynamics in her character, which those around her barely perceive, that make Fanny's life into a Shakespearean tragedy, even if it does not lead to her social downfall. Separating Fanny's personal fate from her social success is part of Jane Austen's critique not only of the social novels of her period, which do not go much farther than define a happy ending as the achievement of social success, but also are part of Jane Austen's critique of Shakespeare, who insisted on correlating personal and social tragedy, when the truth of the inviolable and separated self is that the lack of a social tragedy is only incidentally connected, if not irrelevant, to what is happening in the privacy of a soul.

Fanny emerges as the protagonist of a Shakespearean Jacobean tragedy, not because of her rise in society, or its connection to her fall (since there is no fall) but because of her difficulties in accepting the idea of a marriage to Henry Crawford once it has been settled to the satisfaction of everyone but Mrs. Norris, and before the family is itself sent into imbalance by the elopement of Maria and Henry and the subsequent acceptance of Fanny into full membership in the family. At that point, Fanny is no longer the subject of condescension, but a significant personality who is no longer judged or encumbered by her ungainly manners. Her major fault seems to be the minor one of showing too much deference to her prior position, when others believe, for the moment, that she ought to feel more secure than she does.

It is from this elevated position, and the assumption of family responsibilities that supposedly goes along with it, that she had faced the prospect of Henry Crawford as a suitor. Her rejection of the match, which would seem to bring great good to the family as well as herself, since it is the kind of contribution women can be expected to make to the salvation of the family's fortunes, is only explicable to Sir Thomas as a throwback to prior times, when Fanny might have been expected to have the hesitancy appropriate to a less elevated position. Sir Thomas is willing enough to excuse her response, at least this once. But there is something more in her hesitancy, and it stands beyond issues of class and manners.

By any real world standards, Henry is not at all a bad catch. He says enough things to make this clear. He is, first of all, the only one who shows any interest in improving the land. He actually has some contact with those who oversee his estate, and has made something of a study of "improvements", which is a catchword with the modernizing gentry, raised as they are in a land of steam and canals. Henry, moreover, is willing to be guided by Fanny in how he deals with the land under his control, to accept her judgment about the moral way to deal with his dependents. This is not only more than anyone else is willing to do; it is more than could even occupy their imaginations as a possibility.

Henry also has no trouble we know of in accepting Fanny despite her inferior position. At first interested only in flirting with her, he is the first to notice her even for this potential, because that in itself provides a kind of equality with Julia and Maria, who are far more eligible creatures. His lack of condescension to Fanny and her family, which is more than the Bertrams can manage towards her for a very long while, is so important that Jane Austen pauses to enter the mind of Henry, something she rarely does with her characters, to note that he feels deeply satisfied by the opportunity his wealth provides to give William, who is one of Fanny’s brothers, a horse to ride, which he thinks is little enough a rich man can do for someone who is so admirable because he has devoted his life to doing something substantial. This is not only something the others would not do; it is something only Henry would even contemplate doing.

Certainly Henry is a flirt, first with Maria, and then with Fanny. But it is to be said for him that he did not choose to flirt with Julia, the one who had been assigned to him by order of precedence. Henry is a romantic man. He found Maria attractive, and was encouraged enough to believe that she was not only unhappy with her affianced but would consider him in place of Mr. Rushworth. (Dickens is not alone in identifying people through their names. Everyone rushes to identify Mr. Rushworth's worth by his wealth.) Choosing Henry over Rushworth would mean a sacrifice of income to Maria, but the marriage to Rushworth was so clearly sentimentally unsuitable that only a temporary separation from Henry was enough to make Maria angry enough to lose her judgment, and insist she would marry Rushworth, even though her father gives her every leave to get out of the marriage if she would only say she wanted to. But Maria is not capable of knowing that there are occasions when words are real, have consequences for her life as well as the lives of others, or to appreciate that her father had offered her a chance to save herself from the marriage, to find a safe anchorage for her soul elsewhere. In this, Jane Austen follows Shakespeare's idea that the right marriage is a sort of salvation.

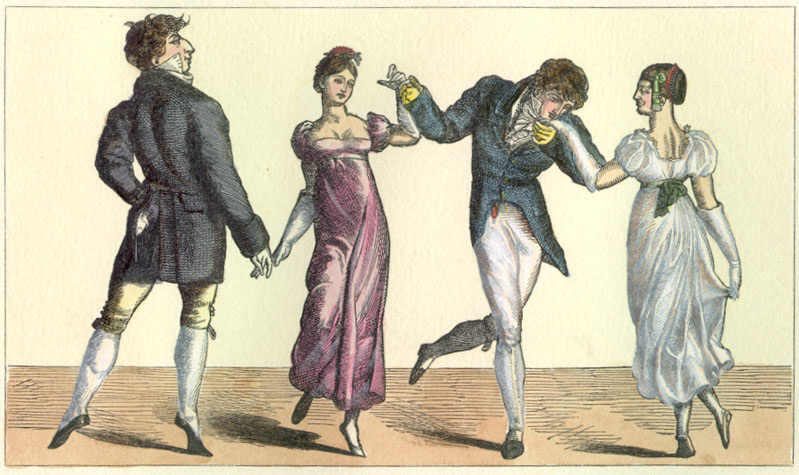

Henry turns his attention to Fanny. This is not as dishonorable as the Bertrams, or Fanny especially, take it to be. Henry had come from London society, which has different meanings for flirtations. Not every one of them are meant as courtships. But, as is generic in Shakespearean love matches, what begins in innocence turns serious. The person who had not been expected to become the beloved turns out to become so.

A Shakespearean reversal should not surprise Fanny who has all along wanted her own sisterly relation with Edmund to turn to love. The suspense over whether Fanny will fall from grace in the Bertram household is joined as a plot motif to the suspense over how the relationship between Fanny and Edmund will turn out. How will she deal with her possessiveness when he finally marries someone else, or how can she possibly arrange for him to find her a love interest? Jane Austen makes sure that the reader sympathizes with Fanny's feelings toward Edmund, so why is it so wrong to suppose there might be a different sort of plot that unfolds, with Henry turning from a flirt into a devoted and sincere suitor for Fanny? That ending would be appropriate if “Mansfield Park” were only a novel of upward mobility, but it is less so because “Mansfield Park” is also about how the intensity of feeling can displace an objective evaluation of things, so that Fanny could except a transformed Edmund from her moral scruples, because her heart warms to him, but cannot accept Henry transformed by his love for her, since she does not respond to his presence as he does to her’s.

Henry's proclamations of devotion to Fanny only seem empty hyperbole when looked at from the outside. That his transformation has been earned by the love of a woman is supported by the fact that he takes her good qualities so seriously, not just as virtues the rest of the family can recognize, but as the expressions of a self, and so the basis for romantic love rather than merely respect. Moreover, these qualities are recognized by him as more essential than her obvious deficiencies as a person without social or economic standing who also combines a minimum of personal attractiveness with a somber and frightened character that rejects all opportunities in the name of circumspection. The concern Edmund and others have that she should not over exert herself is not a false concern directed at the weaknesses attributed to all women, but is specific to Fanny, since the other young women in the family are not treated in that way.

Jane Austen has also provided a precedent for Henry's devotion to Fanny that would make it more plausible if the reader were not seduced into Fanny's way of thinking about things. Fanny does not think the persistent devotion of Edmund to Mary makes him unsuitable to marry Mary. Rather, she thinks his persistence likely to pay off, and that Mary will give in to a marriage that she does not deserve. Why is the same not true of Henry, whose persistence does not seem as clouded as Edmund's is to the character of the woman he is courting? Henry does not praise Fanny for virtues she does not believe herself to have, while Edmund is regularly flattering Mary by describing her in terms that Fanny thinks grossly untrue. But this parallelism does not enlighten Fanny about her relation to Henry, or move her to speak to Edmund about Mary's shortcomings, which as a sister she would be called upon to do.

Henry's final lapse from grace is also more ambiguous than the Bertrams notice, though Jane Austen gives the reader reason enough to suspect that the whole thing had gotten out of hand. Henry seems to have tried to be loyal to Fanny despite her continuing lack of encouragement. Austen lets the reader know that Fanny wanted Henry to persist, but how was Henry to know this? It is not surprising that his interest in Maria is rekindled. (Maria is one of Sir Thomas’s daughters, in case you forgot; there are a lot of characters to keep track of in “Mansfield Park”.) Maria seems hardly at all to be living with her husband anymore. At the outset, it seems, the affair between Maria and Henry was supposed to have been discreet, but someone tattled. Fanny, unlike Mary, chooses to see this as a moral melodrama rather than a moral tragedy. For Fanny, social lapses are still more important than matters of character.

That is because Fanny has learned, if anything, that she gets what she wants only through patience, that she is best served when she holds out against temptation. That is what got her through the years at Mansfield Park, that is what got her through the play, and that is what she expects will get her through the present crisis. For what she wants, which she confesses to herself only reluctantly, is Edmund, nothing less. Fanny sees herself as a kind of Romantic heroine because she will never compromise this goal, even if it means that she never married, and even if she takes the secret of her heroism to the grave. Jane Austen repeatedly reminds the reader that Edmund was the preoccupation that allowed Fanny to remain largely unaffected by the glamour and flattery of Henry, and that no one knew this but herself, in spite of everyone at Mansfield Park and elsewhere spending so much of their lives dissecting one another's motives.

The reason that her attachment to Edmund is unnoticed is because it is awfully close to being incestuous. She had lived with him as a sister for so long that everyone had forgotten Mrs. Norris warning that her proximity to the young men of the house might make her a decidedly unsuitable match for one of them. Sir Thomas, who is usually so careful about controlling social arrangements so that only those occasions for flirtation which he thinks are suitable are allowed, proceeds to dismiss these concerns out of a Squire Western liberality. He insists on drawing a strong line of reason between a paranoid view of class relations, which is bad, and the prudence with which powerful social forces need handling, which is good.

Confronted with Fanny's perversity about the offer of marriage from Henry, Sir Thomas for a moment considers that Fanny might be interested in Edmund, but quickly dismisses it as something of which it would be unworthy to speak. This, in sharp contrast to his willingness to speak to Maria of breaking off her own engagement, suggests that he is not concerned about speaking candidly about the advantages and disadvantages of a particular marriage, but that there is something beyond that in speaking of a possible combination of Fanny and Edmund.

And there is indeed something incestuous about the interest of Fanny in Edmund. We have here the reverse of the situation in “Tom Jones”, where Tom did not know that he was flirting with his real mother. Fanny knows that Edmund is not her real brother, but she does not see that her interest in him is inappropriate because he has been like a brother to her. She saw him within the confines of the family and so she had been privy to his confidences, and had counted on his emotional support during family battles. She feels comfortable with him, as she might with a brother.

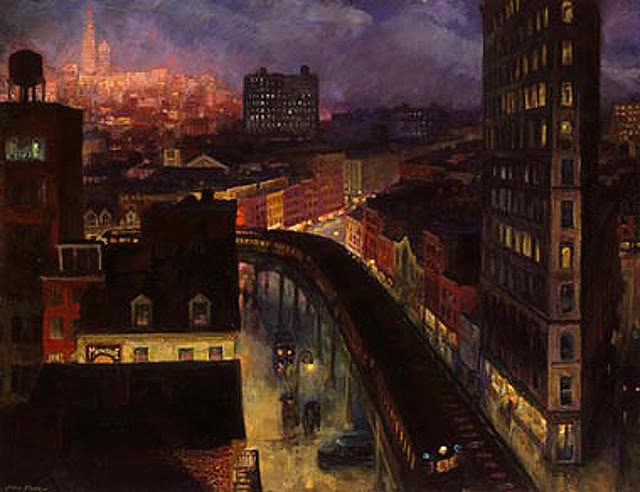

The problem with courtship at country estates like Mansfield Park is that husbands are selected as a result of a few meetings on formal occasions with those few eligible men who come from elsewhere. These are slim pickings, similar to those of the country gentry in Tolstoy or Chekhov. These men, moreover, seem unpleasant. They are characters out of Rawlinson: garrulous, self-flattering, and given to the usual vices of country gentlemen, such as drinking, horses and, one presumes, women. Edmund seems immune to those diversions. He seems much more comfortable, familiar. And that may well be why there is an incest taboo: to make people choose people who are not already in the household, because otherwise the family itself would be an emotional cauldron that could not contain its de-domesticated passions, and because people will be able to get outside their own family's peculiarities only by finding someone from outside it.

This Fanny seems unable to do, for the good reason that men who talk inelegantly and wildly, as most men do, are indeed unattractive, but also for the bad reason that she is unwilling to risk the emotional comforts of the family she has settled with at Mansfield Park. In more modern terms, Fanny seems to suffer sexual anxiety: she is unable to see herself consummating a relationship with someone so gruff and loudmouthed and healthy as the men to whom she is introduced, and would prefer to settle for an easier relation with either her real brother in a small cottage or else in a real marriage to her adopted brother. Marriage, for Fanny, is a kind of impossible safe haven of the sort she had made for herself at Mansfield Park. Why should she give it up? The country set may be quite willing to refer to sexual sentiments as motives-- characters regularly comment on who is attractive and who is not-- but language and custom do provide excuses for not facing up to the challenge of the deepest emotions, much less those perverse passions which do not speak their name in any society.

Isabella, in “Measure for Measure”, is not able to sacrifice her virginity for her brother because, Shakespeare suggests, this is too much evocative of her real feelings. She is saving herself not for an imaginary lover, but for the specter and thought of her brother, and so sleeping with another for his sake would be an irony that cuts too close and therefore must be rejected. A similar Freudian reading, by which the truthfulness of a juxtaposition calls forth repression, applies to Fanny, who is willing to reject all men because no man can be as good as the brother she has adopted, unless she makes the leap of faith which romance would require and passion would urge.

She is finally brought back into the family, after having been pointedly left out of all the developments that sealed the family's fate, oblivious to the possibility that she may have been kept out because her own influence toward moralistic solutions which hide her own needs was no longer admired. She is brought back into the picture only when the disasters have piled up to the point that there is no hope for the family, and the eventual marriage of Fanny and Edmund is now acceptable because it is a kind of funeral, the left over pieces matched up as a mockery of Shakespearean pairings, or, to use another resonance, like Gertrude's marriage to Claudius, too close to a funeral, except that this one is transformed into a kind of joy, a wish about a future, by the family's needs, by Fanny's obtuseness, and by Jane Austen's sense that marriage is more the hope of salvation than the reality of it.

Fanny's most significant tragic flaw, then, is more general than her incestuous feelings about Edmund. Fanny is not only passive before events because she is circumspect, which is an admirable trait, or because she is driven by a pathological wish that the world come to her on her own terms, which is understandable and unremarkable, but also out of a profound misreading of social relations as something other than a place where choices have to be made, some balance of advantages and disadvantages chosen over another balance of advantages and disadvantages. She does not make decisions because she acts as if she is beyond life, a member of the moral rather than the actual world, when marriages and family relations are actual events to which morality is applied rather than a platform from which to condemn reality.

Jane Austen encourages the reader, however, to engage in a healthy sense of suspense over the on-the-one-hand, on-the-other-hand choices, which cannot be usefully resolved either way, but are nonetheless part and parcel of the human condition. “Mansfield Park” and the emotions it invoke therefore stand, in true Shakespearean style, as a critique of the central character of the book, just as “Hamlet” is a critique of the self-consciousness of Hamlet through its exploration of the way people come to master their own self-consciousness and somehow find ways to continue to live-- even after watching plays about self-consciousness.

Fanny makes into a tragedy what was simply the melodrama of every marriage choice. The genre of domestic romance has been elevated into tragedy by demonstrating that to give domestic romance tragic reverberations is itself the source of tragedy for the characters, however illuminating it is to the reader who can catch these reverberations but succeeds in reading the book properly only by returning it to the precincts of a domestic romance. Such a Shakespearean paradox based on the relation of the fiction to reality is required to unravel Fanny, who will not settle when any choice is a settling for one thing rather than another. She has made herself outside the remove of ordinary life, and that is tragic, a turn on Shakespeare, since the tragedy lies not only in the dissolution of a family rather than in any single death, but in the inability of a character who is made the representation of the moral and yet romantic soul, to imagine herself in any ordinary real life pairing at all, but who subverts reality into becoming a copy of her fantasy life.