Being “theatrical” means summing up plot or character with a single gesture so that the audience can take it in and move on. That happens throughout Broadway musicals and is epitomized by Bert Lahr saying that a doctor’s office sketch should not begin with a long exposition of the motivations for being there but with the simple line “Here we are in the doctor's office”. The price of such brevity is that there is no development through dialogue and action of the mood and the circumstances that justify the situation that is to be unfolded through subsequent dialogue and activity. Irving Thalberg is supposed to have told a screenwriter that you don’t need ten pages of dialogue to establish that a man and his wife are not getting along; just show her giving him a glare when he gives a look at a pretty young woman getting out of an elevator the three of them have shared. Thalberg was praising theatricality but that doesn’t do justice to the drama of a situation, where there is an explanation of how people became embedded in their situations, that regarded as something of significant interest, that ten pages of dialogue about a couple on the rocks telling something about this particular relationship and about such relationships in general. Drama has to do with an appreciation of the nature of a conflict while theatricality simply reveals and maybe not very well that the conflict exists. I am thinking of the original production of John Osborne’s “Look Back in Anger” on Broadway in the Fifties. The first act opens with a woman in a slip ironing her boyfriend's shirt. The second act opens with a new girlfriend also standing in her slip at the ironing board. The audience laughed. They got the joke and the revelation that the girlfriend got treated the same way whomever she was. That was the heart of the drama and it was offered up with great theatricality.

Read MoreThe Origins of Romance-I

Romance is when a person regards a sexual partner or a prospective sexual partner with a fascination that renders any number of aspects of the person—the way a woman poses her head, the way a man strides across a room—as so engaging that the lover wants to remain in the company of the beloved for a very long time— or as it is put in the exaggerated rhetoric of romance, “forever”. This engagement with another person licenses the lover to attribute to the beloved any number of positive qualities such as loyalty, attraction, compassion, intelligence and so on, though it also licenses the lover to recognize the failings of a lover— his or her meanness or anger or duplicity-- without necessarily breaking the bond that ties them together emotionally and may simply mean that a lover understands that his or her beloved is a termagant or a bully or a nag or distracted. Love does not mean the forgiveness of all, only the acceptance of all, love being a way to think that the intensity of sexual passion is a window into the soul of the beloved.

Read MoreStorytelling at Oscar Time

Hollywood has always been the preserve of middle brow sensitivities. Charlie Chaplin was sentimental; the very talky dramas of the Thirties and Forties testified to the sanctity of middle class life (think of “The Best Years of Our Lives”); the Seventies, given their taste for epics, translated the gangster film into a family tragedy (think of “The Godfather” trio of movies). And so it goes on, people without much education treating Hollywood as their canon of great literature, quoting “Casablanca” or”The Wizard of Oz” as part of the collective wisdom they have absorbed into their own heads, using those stories and phrases to capture events in their own fantasy and actual lives, just as Shakespeare or Dickens serve that function for a more educated audience. And so it is fair to ask a deep aesthetic question after this year’s Oscars, which made Koreans the latest group to move into the spotlight, just as in the past Hollywood acceptance marked the passage of Jews, Italians and African Americans into the assimilated parts of the nation, even if women, one such group vieing for inclusion, still consider themselves as having a way to go, however much the women’s point of view has driven story lines from at least the Thirties Warner Brothers’ musicals to the Nora Ephron romantic comedies of the Nineties.

Read MoreComedy and Tragedy in "Pride and Prejudice"

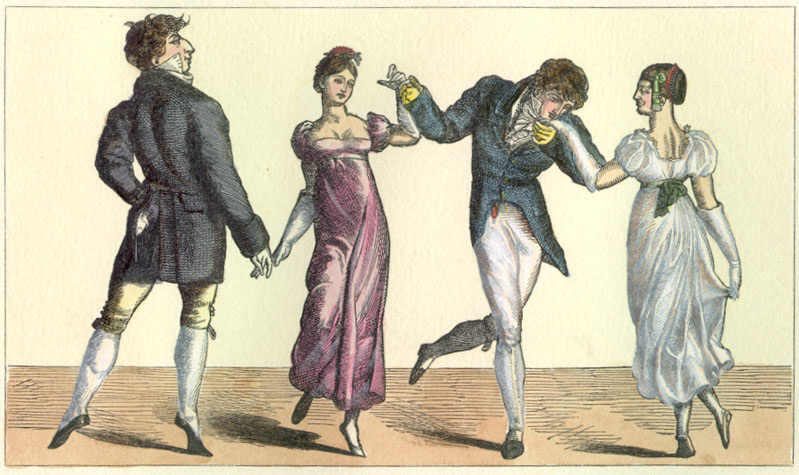

“Pride and Prejudice”, as well as the other Jane Austen novels, can be appreciated for their sparkling dialogue and their vivid characters and the clear narrative lines that manage to balance off multiple characters, as well as for the very detailed portrayal of the world of the country gentry in Regency England. The truth, however, is that Jane Austen accomplishes much more than that. She provides an objective appraisal of the human condition that you will find nowhere else except in Shakespeare and in some of the books of the Old Testament, notably in “Genesis” and the story of David as told in “Samuel I and II”. Among other things, Austen takes a perfectly objective approach to her characters, explaining what they are with utmost clarity, warts and all, while most novelists, including Dickens, take sides, preferring their heroes to their villains, while Jane Austen is beyond that, and that in itself is very liberating as it calls forth in a reader the ability also to be beyond judgment. People are what they are. Deal with it. Emma, for one, is less talented, and more superficial, than others in the Jane Austen repertoire. Elizabeth Bennet, for example, must have been an insufferably awkward and outspoken young woman at the beginning of "Pride and Prejudice", just as Darcy thought her to be, but she also has appeal as an extremely intelligent and firm and deeply moral person, which also appealed to Darcy, who has to be given credit for seeing her as a diamond in the rough. All of Jane Austen's heroines as flawed but not unworthy just because of that. Their flaws could have made them into tragic heroines, as in Ibsen, but instead Austen gives life to each of them so that they become precious souls instead of doomed creatures.

Read MoreThe Political Doldrums

Everyone I know is depressed about politics. Maybe it is because we are in mid-winter, and so caught up in Shakespeare “A Winter’s Tale”, where people cannot help but engage in sin for no reason at all and so, one can surmise, are cursed with original sin. Maybe it is because we are almost up to the Iowa caucuses and no Democratic candidate has caught fire, Democrats, as the axiom has it, wanting to fall in love with a candidate while Republicans only care about who is next in line. The Democratic primary candidates all seem unsuited for the role of someone who offers a new day. Warren and Sanders are too Left; Biden is too old; Buttigieg is too young; and Amy Klobuchar seems to be everybody’s idea of a perfect vice-presidential candidate: charming, left of center, a good ticket balancer-- even if Blacks may demand that place on the ticket-- but too narrow a vision in that winning every county in Minnesota is not exactly what you want to go on a bumper sticker.

Read MoreHow The Arts Evolve

At least in the history of the modern world, high brow forms of art and culture evolved out of popular forms of entertainment. Every genre came to provide deep feelings and insights into the nature of life, those experiences presented in a beguiling way: with suspense, or local color, or characters worth noticing. The modern drama from Shakespeare through Genet, for example, was propelled out of the biblical plays performed in the English countryside and in churches, those allegorical and simplified dramas showing their abiding presence in the tragic comedies of the theatre of the absurd and, in America, in the moralizing of O’Neill and Williams who, in spite of the depth of character they also provided, constructed dramatic arcs through which people got their just deserts, just as had been true in ”Everyman”. But that process of high culture growing from popular culture, and not just in the theatre, had not been apparent during the two cultural periods known as “Modernism” (circa 1895-1938) and “The Age of Anxiety” (circa 1938-1968) because of the predominance of the elitist or experimental novel, like those of Joyce and Kafka, and the paintings of, for example, Picasso and Rothko, the literature and art inaccessible to the popular reader and viewer, and so we are likely to still think that the present cultural period, known as “Contemporary” or “Postmodern” is, like its two predecessor periods, elitist in origin, when in fact all of these periods were ones in which culture had its roots in the popular culture rather than in top down culture.

Read MoreFrom Whence Contemporary Authority Flows

Max Weber defined “authority” as the ability to convince people to follow your lead, which was different from its companion concept, ”power”, which is the ability to get people to do what you want even if they don’t want to. One of the main and perhaps original sources of that thing he called “power” was what Weber labelled as “charisma”, which meant the ability of a person to be so compelling a figure that people would do what he said, they somehow mesmerized because of that person’s personal appeal. And so Hitler was charismatic, even while FDR, however charming, was also the bearer of the TR-Wilsonian ideology, somewhat modified, that the purpose of government was to make the lives of people better and so to expand the role of government to accomplish that end, a principle Democrats come back to even if not in so many words, it certainly different from the alternative principle, which is that the purpose of government is not to make things better but to put as many brakes as possible on progressive impulses so as to further feather the nests of already rich people.

Read MoreTo Engage with Judy Garland

A. O. Scott, the NY Times movie critic, was right on the mark when he said in his review of “Judy” that the movie really wasn’t that great but that Renee Zellwegger had done such a star turn portraying Judy Garland that she was up there for an Academy Award for Best Actress. I would put it differently. Zellwegger doesn’t look like Garland, she doesn’t sound like her, and she doesn’t have her mannerisms, but she puts together a character which makes you think of Judy Garland, which is in keeping with what Zellwegger has said in interviews, which is that her aim was not to imitate Garland but to convey the emotions that went along with her. The movie itself, however, settles for the usual bio-facts about Garland. She was groomed by Louis B. Mayer to be a star, she took diet pills and sleeping pills from an early age and thus became a life-long addict, she was a car wreck in that she gave erratic performances and often didn’t show up on time, and the movie even threw in another part of the Garland legend, which is that she became an icon for her gay followers, all of these facts following from and in the service of an Achilles like dilemma to have a dazzling life as a performer even if it meant her personal life would be very rough, a pledge she did not regret until the end of her life when she preferred to see herself as a mother than as Judy Garland, the legend.

Read MoreThomas Cole's "The Voyage of Life"

Thomas Cole’s “The Voyage of Life” is a series of four paintings he did in the 1840’s that showed the stages of human development, the first about childhood, the second about youth, the third about maturity, and the fourth about old age. These paintings set out a theory of human development when no theories of that sort would be rendered until the turn into the Twentieth Century and so the four paintings are like Cole’s four paintings on “The Course of Empire” in that they are breaking new intellectual ground and trying to find images to do justice to the insights that Cole offers up even if, I am afraid, he does not in this case do very well at illustrating his conceptions. The paintings in the series are worth consulting because they show us what a muscular intellect can do at starting out an entire field of human inquiry.

Read MoreRembrandt Peale

A single painting tells a story about its subject while the body of work of a painter tells the story of that painter’s life: his moods, how he changes or develops or deteriorates over time, his persistent themes. The body of work is therefore more significant for looking into what a painter is than is any collection of biographical data compiled by some biographer about his love interests, his patrons, his friendships, or the ruminations of himself or the art critics of his time about what his paintings were really about. The same is true of literature. We know how different “Macbeth” is from “Hamlet”, each creating a different world, the first governed by fate and violent action, the second by a self uncertain how and when to take action. And yet the body of Shakespeare’s work tells us all that need be known about the consciousness of its author: how he moves from history to comedy to tragedy to romance, ever trying to contain his tendency to anger. The work is the essence of the author.

A case in point is Rembrandt Peale, son of a well known artist of his time, and even better known in his own right, who was a prolific portrait painter in the early part of the Nineteenth Century. Looking at the body of his work provides a biography of the painter and also how a painter adjusts to changing circumstances that are, for the most part, neither political nor social structural, but cultural in that they have to do with the influences that past painting has on its present practitioner. So let us abandon the view that a painter reflects his time for the view that a painter makes a mark on the painting of his time.

Read MoreThe Power of Metaphor

A metaphor is supposed to be a word that is associated with what it represents because of some similarity between what the word refers to and what the word is taken to represent. Love is like a madness because it can come up suddenly, becomes an obsession and can’t easily be explained. So a metaphor can consider and evoke other characteristics of the object to be explained than the ones that are its essential characteristics, whatever might be those essential characteristics. That is why a metaphor is so liberating: it gives associations rather than a denotative definition that allows classifying objects always or nearly always accurately. But love is also supposed to be like a red, red rose. There are similarities here too in that a rose is beautiful and delicate, which is often said of one’s beloved, as is the fact that a lover can be thorny. So a person can go very far afield or be very creative when constructing a metaphor, and so the metaphor is more in the mind of its author than in the object represented. Anything can turn into a metaphor, which means that a metaphor is really a symbol, which means that it is arbitrarily or conventionally associated with its object. A recent Nova broadcast was eerie in its account of the inner planets because it treated Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars as if they were human in that these masses of rocks had their moments in the sun, literally, in that they had water oceans before the ever greater heat of the sun robbed them of their atmospheres and their water and made them “dead” planets, even though, of course, planets are not people. The power of metaphor is an important way of understanding the meaning of texts and also prompts consideration of how writers limit the power of metaphor in the service of creating truth rather than opinion.

Read More22/23- The Gospels as an Epic Comedy

Mark Van Doren taught me a long time ago that an epic was episodic in that there were many events that filled in the space between the initial action and the final action. These events did not so much move the action forward as take place within the environment created by the story’s parameters. From that I conclude, upon many years reflection, that epics are different from novels in this respect (as well as many other ways) because while there may be digressions and subplots in novels, much of the plot in novels is used to move the story forward. By these lights, I also conclude, “Exodus” is not an epic. It is too tightly plotted for that. It is more of what Vico would call sacred history, which means that it shows what had to happen rather than what might have happened or what in fact did happen. The Gospels are another sacred history because there too the narrators are recounting what had to have happened and did while the narrator of a novel is just along for the ride, for the telling of the tale, rather than the authoritative voice that commands belief in the inevitability of what is unfolded by a story or set of stories.

Read MoreJohnson's Dictionary

The importance of Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary is not that it was one of the first or that he had some piquant definitions but that it took a very different approach to language than is generally taken by philosophers. Samuel Johnson does something very radical in his dictionary. He posits the idea that for any word, whether simple or complex, everyday or esoteric, there is another word or string of words that can be generated in English that is its equivalent in meaning. Johnson provides some forty thousand examples as proof of his proposition. That is a remarkable thing to claim about language. However much it expands, whatever new words are added to its vocabulary, there is some other set of words it can be mapped to. Why this is the case, Johnson does not explain. He was not that kind of thinker. But he was a student of language and so could invent or find, take your pick, these equivalences which made language not a closed system in that words could only refer to other words, but an open system, in that new words could always be meaningful because they could be referred to old words. This is a characteristic of language in general, that it expands in this way, and it is not a characteristic which holds for other systems of thought.

Read More4/23- Noah the Technologist

Noah was a good enough engineer, whether he got the plans from God or dreamed them up himself under the inspiration of God, to correctly execute these very ambitious plans. The plans are spelled out in detail. The ark is to have three levels. It is to be caulked both inside and outside. It is to be three hundred cubits long, fifty cubits wide and thirty cubits high. The dimensions of the ark are given so distinctly that they serve the literary purpose, of course, of concretizing the description and so make it as if it happened. But this is an interesting set of descriptors. “Genesis” could have said large or very large or as tall as a cedar of Lebanon or some other metaphor for size. “Genesis” does tend to exaggerate when it gives particular numbers, as when it gives the ages of the generations between Adam and Noah. That makes the story legendary: an exaggeration of what might have happened in the past rather than treating the past as having a very different set of processes than does the present, which is what happens when a mythology is created. There seems to be a different reason for concretizing here in the Noah story.

Read More6/9: The Tragedy of Incest

Fanny Price, the anti-heroine of “Mansfield Park”, has character traits that have been helpful in moving her up in the world to the extent to which she has but which work against her rising any further. Such an irony is sufficient for an Eighteenth Century domestic novel. There are, however, more troubling dynamics in her character, which those around her barely perceive, that make Fanny's life into a Shakespearean tragedy, even if it does not lead to her social downfall. Separating Fanny's personal fate from her social success is part of Jane Austen's critique not only of the social novels of her period, which do not go much farther than define a happy ending as the achievement of social success, but also are part of Jane Austen's critique of Shakespeare, who insisted on correlating personal and social tragedy, when the truth of the inviolable and separated self is that the lack of a social tragedy is only incidentally connected, if not irrelevant, to what is happening in the privacy of a soul.

Fanny emerges as the protagonist of a Shakespearean Jacobean tragedy, not because of her rise in society, or its connection to her fall (since there is no fall) but because of her difficulties in accepting the idea of a marriage to Henry Crawford once it has been settled to the satisfaction of everyone but Mrs. Norris, and before the family is itself sent into imbalance by the elopement of Maria and Henry and the subsequent acceptance of Fanny into full membership in the family. At that point, Fanny is no longer the subject of condescension, but a significant personality who is no longer judged or encumbered by her ungainly manners. Her major fault seems to be the minor one of showing too much deference to her prior position, when others believe, for the moment, that she ought to feel more secure than she does.

It is from this elevated position, and the assumption of family responsibilities that supposedly goes along with it, that she had faced the prospect of Henry Crawford as a suitor. Her rejection of the match, which would seem to bring great good to the family as well as herself, since it is the kind of contribution women can be expected to make to the salvation of the family's fortunes, is only explicable to Sir Thomas as a throwback to prior times, when Fanny might have been expected to have the hesitancy appropriate to a less elevated position. Sir Thomas is willing enough to excuse her response, at least this once. But there is something more in her hesitancy, and it stands beyond issues of class and manners.

By any real world standards, Henry is not at all a bad catch. He says enough things to make this clear. He is, first of all, the only one who shows any interest in improving the land. He actually has some contact with those who oversee his estate, and has made something of a study of "improvements", which is a catchword with the modernizing gentry, raised as they are in a land of steam and canals. Henry, moreover, is willing to be guided by Fanny in how he deals with the land under his control, to accept her judgment about the moral way to deal with his dependents. This is not only more than anyone else is willing to do; it is more than could even occupy their imaginations as a possibility.

Henry also has no trouble we know of in accepting Fanny despite her inferior position. At first interested only in flirting with her, he is the first to notice her even for this potential, because that in itself provides a kind of equality with Julia and Maria, who are far more eligible creatures. His lack of condescension to Fanny and her family, which is more than the Bertrams can manage towards her for a very long while, is so important that Jane Austen pauses to enter the mind of Henry, something she rarely does with her characters, to note that he feels deeply satisfied by the opportunity his wealth provides to give William, who is one of Fanny’s brothers, a horse to ride, which he thinks is little enough a rich man can do for someone who is so admirable because he has devoted his life to doing something substantial. This is not only something the others would not do; it is something only Henry would even contemplate doing.

Certainly Henry is a flirt, first with Maria, and then with Fanny. But it is to be said for him that he did not choose to flirt with Julia, the one who had been assigned to him by order of precedence. Henry is a romantic man. He found Maria attractive, and was encouraged enough to believe that she was not only unhappy with her affianced but would consider him in place of Mr. Rushworth. (Dickens is not alone in identifying people through their names. Everyone rushes to identify Mr. Rushworth's worth by his wealth.) Choosing Henry over Rushworth would mean a sacrifice of income to Maria, but the marriage to Rushworth was so clearly sentimentally unsuitable that only a temporary separation from Henry was enough to make Maria angry enough to lose her judgment, and insist she would marry Rushworth, even though her father gives her every leave to get out of the marriage if she would only say she wanted to. But Maria is not capable of knowing that there are occasions when words are real, have consequences for her life as well as the lives of others, or to appreciate that her father had offered her a chance to save herself from the marriage, to find a safe anchorage for her soul elsewhere. In this, Jane Austen follows Shakespeare's idea that the right marriage is a sort of salvation.

Henry turns his attention to Fanny. This is not as dishonorable as the Bertrams, or Fanny especially, take it to be. Henry had come from London society, which has different meanings for flirtations. Not every one of them are meant as courtships. But, as is generic in Shakespearean love matches, what begins in innocence turns serious. The person who had not been expected to become the beloved turns out to become so.

A Shakespearean reversal should not surprise Fanny who has all along wanted her own sisterly relation with Edmund to turn to love. The suspense over whether Fanny will fall from grace in the Bertram household is joined as a plot motif to the suspense over how the relationship between Fanny and Edmund will turn out. How will she deal with her possessiveness when he finally marries someone else, or how can she possibly arrange for him to find her a love interest? Jane Austen makes sure that the reader sympathizes with Fanny's feelings toward Edmund, so why is it so wrong to suppose there might be a different sort of plot that unfolds, with Henry turning from a flirt into a devoted and sincere suitor for Fanny? That ending would be appropriate if “Mansfield Park” were only a novel of upward mobility, but it is less so because “Mansfield Park” is also about how the intensity of feeling can displace an objective evaluation of things, so that Fanny could except a transformed Edmund from her moral scruples, because her heart warms to him, but cannot accept Henry transformed by his love for her, since she does not respond to his presence as he does to her’s.

Henry's proclamations of devotion to Fanny only seem empty hyperbole when looked at from the outside. That his transformation has been earned by the love of a woman is supported by the fact that he takes her good qualities so seriously, not just as virtues the rest of the family can recognize, but as the expressions of a self, and so the basis for romantic love rather than merely respect. Moreover, these qualities are recognized by him as more essential than her obvious deficiencies as a person without social or economic standing who also combines a minimum of personal attractiveness with a somber and frightened character that rejects all opportunities in the name of circumspection. The concern Edmund and others have that she should not over exert herself is not a false concern directed at the weaknesses attributed to all women, but is specific to Fanny, since the other young women in the family are not treated in that way.

Jane Austen has also provided a precedent for Henry's devotion to Fanny that would make it more plausible if the reader were not seduced into Fanny's way of thinking about things. Fanny does not think the persistent devotion of Edmund to Mary makes him unsuitable to marry Mary. Rather, she thinks his persistence likely to pay off, and that Mary will give in to a marriage that she does not deserve. Why is the same not true of Henry, whose persistence does not seem as clouded as Edmund's is to the character of the woman he is courting? Henry does not praise Fanny for virtues she does not believe herself to have, while Edmund is regularly flattering Mary by describing her in terms that Fanny thinks grossly untrue. But this parallelism does not enlighten Fanny about her relation to Henry, or move her to speak to Edmund about Mary's shortcomings, which as a sister she would be called upon to do.

Henry's final lapse from grace is also more ambiguous than the Bertrams notice, though Jane Austen gives the reader reason enough to suspect that the whole thing had gotten out of hand. Henry seems to have tried to be loyal to Fanny despite her continuing lack of encouragement. Austen lets the reader know that Fanny wanted Henry to persist, but how was Henry to know this? It is not surprising that his interest in Maria is rekindled. (Maria is one of Sir Thomas’s daughters, in case you forgot; there are a lot of characters to keep track of in “Mansfield Park”.) Maria seems hardly at all to be living with her husband anymore. At the outset, it seems, the affair between Maria and Henry was supposed to have been discreet, but someone tattled. Fanny, unlike Mary, chooses to see this as a moral melodrama rather than a moral tragedy. For Fanny, social lapses are still more important than matters of character.

That is because Fanny has learned, if anything, that she gets what she wants only through patience, that she is best served when she holds out against temptation. That is what got her through the years at Mansfield Park, that is what got her through the play, and that is what she expects will get her through the present crisis. For what she wants, which she confesses to herself only reluctantly, is Edmund, nothing less. Fanny sees herself as a kind of Romantic heroine because she will never compromise this goal, even if it means that she never married, and even if she takes the secret of her heroism to the grave. Jane Austen repeatedly reminds the reader that Edmund was the preoccupation that allowed Fanny to remain largely unaffected by the glamour and flattery of Henry, and that no one knew this but herself, in spite of everyone at Mansfield Park and elsewhere spending so much of their lives dissecting one another's motives.

The reason that her attachment to Edmund is unnoticed is because it is awfully close to being incestuous. She had lived with him as a sister for so long that everyone had forgotten Mrs. Norris warning that her proximity to the young men of the house might make her a decidedly unsuitable match for one of them. Sir Thomas, who is usually so careful about controlling social arrangements so that only those occasions for flirtation which he thinks are suitable are allowed, proceeds to dismiss these concerns out of a Squire Western liberality. He insists on drawing a strong line of reason between a paranoid view of class relations, which is bad, and the prudence with which powerful social forces need handling, which is good.

Confronted with Fanny's perversity about the offer of marriage from Henry, Sir Thomas for a moment considers that Fanny might be interested in Edmund, but quickly dismisses it as something of which it would be unworthy to speak. This, in sharp contrast to his willingness to speak to Maria of breaking off her own engagement, suggests that he is not concerned about speaking candidly about the advantages and disadvantages of a particular marriage, but that there is something beyond that in speaking of a possible combination of Fanny and Edmund.

And there is indeed something incestuous about the interest of Fanny in Edmund. We have here the reverse of the situation in “Tom Jones”, where Tom did not know that he was flirting with his real mother. Fanny knows that Edmund is not her real brother, but she does not see that her interest in him is inappropriate because he has been like a brother to her. She saw him within the confines of the family and so she had been privy to his confidences, and had counted on his emotional support during family battles. She feels comfortable with him, as she might with a brother.

The problem with courtship at country estates like Mansfield Park is that husbands are selected as a result of a few meetings on formal occasions with those few eligible men who come from elsewhere. These are slim pickings, similar to those of the country gentry in Tolstoy or Chekhov. These men, moreover, seem unpleasant. They are characters out of Rawlinson: garrulous, self-flattering, and given to the usual vices of country gentlemen, such as drinking, horses and, one presumes, women. Edmund seems immune to those diversions. He seems much more comfortable, familiar. And that may well be why there is an incest taboo: to make people choose people who are not already in the household, because otherwise the family itself would be an emotional cauldron that could not contain its de-domesticated passions, and because people will be able to get outside their own family's peculiarities only by finding someone from outside it.

This Fanny seems unable to do, for the good reason that men who talk inelegantly and wildly, as most men do, are indeed unattractive, but also for the bad reason that she is unwilling to risk the emotional comforts of the family she has settled with at Mansfield Park. In more modern terms, Fanny seems to suffer sexual anxiety: she is unable to see herself consummating a relationship with someone so gruff and loudmouthed and healthy as the men to whom she is introduced, and would prefer to settle for an easier relation with either her real brother in a small cottage or else in a real marriage to her adopted brother. Marriage, for Fanny, is a kind of impossible safe haven of the sort she had made for herself at Mansfield Park. Why should she give it up? The country set may be quite willing to refer to sexual sentiments as motives-- characters regularly comment on who is attractive and who is not-- but language and custom do provide excuses for not facing up to the challenge of the deepest emotions, much less those perverse passions which do not speak their name in any society.

Isabella, in “Measure for Measure”, is not able to sacrifice her virginity for her brother because, Shakespeare suggests, this is too much evocative of her real feelings. She is saving herself not for an imaginary lover, but for the specter and thought of her brother, and so sleeping with another for his sake would be an irony that cuts too close and therefore must be rejected. A similar Freudian reading, by which the truthfulness of a juxtaposition calls forth repression, applies to Fanny, who is willing to reject all men because no man can be as good as the brother she has adopted, unless she makes the leap of faith which romance would require and passion would urge.

She is finally brought back into the family, after having been pointedly left out of all the developments that sealed the family's fate, oblivious to the possibility that she may have been kept out because her own influence toward moralistic solutions which hide her own needs was no longer admired. She is brought back into the picture only when the disasters have piled up to the point that there is no hope for the family, and the eventual marriage of Fanny and Edmund is now acceptable because it is a kind of funeral, the left over pieces matched up as a mockery of Shakespearean pairings, or, to use another resonance, like Gertrude's marriage to Claudius, too close to a funeral, except that this one is transformed into a kind of joy, a wish about a future, by the family's needs, by Fanny's obtuseness, and by Jane Austen's sense that marriage is more the hope of salvation than the reality of it.

Fanny's most significant tragic flaw, then, is more general than her incestuous feelings about Edmund. Fanny is not only passive before events because she is circumspect, which is an admirable trait, or because she is driven by a pathological wish that the world come to her on her own terms, which is understandable and unremarkable, but also out of a profound misreading of social relations as something other than a place where choices have to be made, some balance of advantages and disadvantages chosen over another balance of advantages and disadvantages. She does not make decisions because she acts as if she is beyond life, a member of the moral rather than the actual world, when marriages and family relations are actual events to which morality is applied rather than a platform from which to condemn reality.

Jane Austen encourages the reader, however, to engage in a healthy sense of suspense over the on-the-one-hand, on-the-other-hand choices, which cannot be usefully resolved either way, but are nonetheless part and parcel of the human condition. “Mansfield Park” and the emotions it invoke therefore stand, in true Shakespearean style, as a critique of the central character of the book, just as “Hamlet” is a critique of the self-consciousness of Hamlet through its exploration of the way people come to master their own self-consciousness and somehow find ways to continue to live-- even after watching plays about self-consciousness.

Fanny makes into a tragedy what was simply the melodrama of every marriage choice. The genre of domestic romance has been elevated into tragedy by demonstrating that to give domestic romance tragic reverberations is itself the source of tragedy for the characters, however illuminating it is to the reader who can catch these reverberations but succeeds in reading the book properly only by returning it to the precincts of a domestic romance. Such a Shakespearean paradox based on the relation of the fiction to reality is required to unravel Fanny, who will not settle when any choice is a settling for one thing rather than another. She has made herself outside the remove of ordinary life, and that is tragic, a turn on Shakespeare, since the tragedy lies not only in the dissolution of a family rather than in any single death, but in the inability of a character who is made the representation of the moral and yet romantic soul, to imagine herself in any ordinary real life pairing at all, but who subverts reality into becoming a copy of her fantasy life.

5/9: The Theatricals at Mansfield Park

The transition in “Mansfield Park” from language that is occluded because it is calculated to language that is, by and large, in the clear because the characters have need of a language whereby they can express who they are, takes place at the same moment that is the pivotal point for the plot of the novel, which is when Sir Thomas Bertram returns from Antigua. Jane Austen seems to expect her more literate puzzle solvers to catch on to this union of her structural and language leverage points, and so see the Shakespearean allusion as well as the importance for the plot of weaving the change of language into the new developments in the plot, just as she expects her merely attentive reader to solve the puzzle of her characters if some attention is paid to the abundance of clues Jane has so thoughtfully provided to help the reader along.

The Shakespeare play that Jane Austen chose to rework as “Mansfield Park” is probably “Measure for Measure”. There, just as in “Mansfield Park”, a heroine who seems devoted to virtue comes to seem perverse because of her seeming unwillingness ever to consider prudence, even to serve, there, the interests of her brother, and in spite of the advice of all those who surround her. There is also an absent nobleman, who has allowed his society to run on its own dynamics, presuming these to be fixed, settled, and self-balancing, only to return to find that things have fallen apart, his society on the verge of some kind of moral anarchy. The general belief is that society can only be restored to its proper balance by the intervention of the returned leader, though it is not clear that he has either the understanding or the will to do so. The audience and the reader are left with the very sour feeling that people keep making messes of their lives, and will continue to do so, and manage to rectify things, if at all, only by redefining relative failure as relative success. Their problems arise not so much from tragic flaws, from their own or the universe's nature, but from thoughtlessness, stubbornness, and other minor vices.

As soon as Sir Thomas appears on the scene on his return from Antigua, there is an immediate change in the meaning of language. Now events which had been frivolous and words which had been meaningless take on their full resonance and meaning all at once, as if everyone had been removed to a higher level of understanding, the veil between illusion and reality suddenly lifted.

It is interesting to contemplate the first emotions people might have felt under this new dispensation. It might have been gladness, reasonability, sentiment, or any number of other emotions thought characteristic of the Eighteenth Century. Instead, the first emotion every character feels is guilt, even down to Fanny, who has least to feel guilty about since she had held out longest against the temptation of doing theatricals, even though she had at the end given in ever so little to it.

Sir Thomas forgives the family immediately, though Jane Austen suggests this has less to do with relenting from a deserved sternness that in his unwillingness to forego the pleasure of his reunion with his family. He does put an immediate end to the festivities, even if Yates, a friend of the family who had first proposed the theatricals, is so crude as to ask why everyone had done such an about face, and wonders what was so wrong with the theatricals, especially since Sir Thomas, perhaps out of a touch of guilt about having cancelled them, decides to give a ball that will serve as a kind of coming out party for Fanny.

The trouble with the theatricals is in part financial. Mrs. Norris is quick to note how much money she saved on the project, so everyone was at the time of their plans aware that they should not spend too much money. Sir Thomas was, after all, away in Antigua to straighten out their finances, and it is to be presumed, though Jane Austen does not say so in so many words, that the family was trying to live frugally until the economic problems were resolved.

There is a larger problem with the theatricals. They are a recipe for license because they allow people to proclaim emotions they do not feel which are of an intimate sort, or even worse, allow people to proclaim private feelings which they do feel, but which are not properly spoken of. The irony of this situation was lost on the characters, though not to the reader, before Sir Thomas' reappearance, but it is sensed as a careless form of liberation afterwards. It is not that the characters did not know before what they knew afterwards, but that they took it all more seriously, with more responsibility, as if now they had to be responsible for their actions when the presiding figure was present but were not responsible for their actions, did not have to act as other than children, when their father was away.

The reader is made ever more aware of the precarious hold morality has on Mansfield Park. Far from secure, morality is always challenged by the immoral ways of the country gentry young folk, the likes of Tom, Sir Thomas’ eldest son, who are always off on some misadventures which they can talk about only in the euphemisms of horseracing. Sir Thomas does not want his family's country respectability to give way to the looser morals of the large country estates or of the city.

The ball for Fanny is not the same thing as theatricals, since it is a real rather than a fancied event, and so people will, if anything, act more properly than they otherwise might. It is also an event where there is sufficient formality and control by the elders so that flirting is kept within its proper bounds of providing indications of interest in pairing off. It is the kind of courtship which allows the passions to present themselves in a useful way, and it takes Sir Thomas' presiding genius to understand the delicate balance of pretense and compromise which allows the passions to be turned to useful arrangements, even if he is eventually to be overcome by his inability to manage things as well as he would have liked.

The play within a play that moves along the plot of the novel or play into which it is interpolated is, of course, an inheritance from “Hamlet”. Shakespeare is also known for his performances-within-performances, where characters go through set piece ceremonies where they each know what role they are supposed to play and, for some reason, fail to act properly. In the plays that precede the great tragedies, these performances are set towards or after the middle of the play and result in its subsequent events, and so function as the play within the play will function. Shylock is so overtaken by his rage that during the trial scene he drops the life long guise of magnanimity which he had adopted for the sake of prudence and so brings down all the evils which his Jewish soul had dreaded, by for once giving vent to his desire for vengeance. He for once holds a gentile to his promise, as he is presumably always held to his despite the entreaties of all the good gentiles that he act with nobility, even if the nobles engage in this performance of Christian virtue only this one time when the life of one of their own is at stake. Henry V, for his part, is remarkably passive, falling back on his old contemplative ways, when he listens to the explanation of his rights to the French throne, and unleashes the war as if he did not in that formal performance of his kingly role have the right to ask his advisors to reconsider, or give them new guidance about ways to deal with the French, who would probably have bartered their daughter for a peace treaty before as well as after the war.

Most of the time, however, the performances come close to the beginning of a play, as if the set pieces, the public occasions, generate the entire play or its most general movement when a key character misreads his role or perversely refuses to play it or somehow has risen beyond it. The intrigue in “Julius Caesar” emerges from the interpretation of what Caesar meant when he three times turned down the throne. Was it merely a performance, or an intention as well? There was nothing Caesar could have done within that performance that would have appeased his opponents. Hamlet suggests the depths of his own misanthropy and his preoccupation with his own cleverness when he plays on the pun of being a son during his formal reintroduction at the Danish court. Othello is better at declaring his love of state and of Desdemona at his formal return to Venice than he is able to avoid personal and social anarchy at the end of the play during the private performance of the confrontation scene he had set up in his mind. And, of course, both Lear and Cordelia both violate and uphold performance standards in the set piece that opens “King Lear”.

Jane Austen has a play within a play as a central moment of “Mansfield Park”, the point of which is that when people feign emotions they really have, as is the case when Maria plays opposite Henry, then people actually do perform the roles they have hesitated to perform in real life, and so reveal themselves more than is discrete, not because it is improper to be so forward, but because it is too emotionally destabilizing to act as if one is acting emotions which are not being merely performed but are in fact felt. People come to recognize themselves in their roles, or if they fail to do so, as is the case with the characters at Mansfield Park, it is not only a sign that they are obtuse, but are, in their own "real" world within the novel, merely prisoners of their roles, unsaved by circumspection and thoughtfulness, which is the virtue Jane Austen saves for herself and, occasionally, bestows on Fanny.

The characters do not know what to make of what they feel because they think they are merely playing roles, rather than displaying their feelings in public. Theatricals are a threat to social order not because they are play, but because they come too close to the truth. They serve the same purpose as a psychoanalytic session: they provide an occasion for the projection of feelings that are otherwise unnamed, and which are not less real because they are not attributed to the players during the dispensation of the performance.

The ball that Sir Thomas prefers to the theatricals is a performance within a performance that contains its own paradoxes and ironies. People at balls know they are feigning roles, while during the theatricals they do not know they are not merely feigning roles. At the ball, everyone cooperates to make Fanny look good, and so they discount what they are doing, though what they do not only succeeds in elevating Fanny's position in society, and her own self-esteem in a realm where, like Othello, she thought herself inadequate, but where her enthusiasms do not seem to create a disaster, her indulgence of her dreams of herself sustained rather than the object of humiliation, but where people do reveal themselves more than they want to, both Henry and Edmund coming off as her especial friends, which leads to the two courtships, one or the other either sacred or profane, that will dominate the rest of the book.

As Shakespeare knew, plays and performances are not fictions, but kinds of reality in which more is revealed than the characters recognize is revealed even if they see and are participants in the revelation. While Shakespeare may consequently have seen theatrics and performances as metaphors for religious conversion, Jane Austen simply regards them as methods and mechanisms for the continuing unraveling of character which is the nature of life in the world, and the ultimate justification of fiction.

4/9: Jane Austen and Shakespeare

Jane Austen was a literary intellectual in the sense that she used literature as a vehicle for writing about life rather than just to amuse readers so that they would buy her books, notwithstanding that her first two novels were satires of the popular genres of her time: the gothic romance and the novel of domestic life. Jane Austen was also an avid follower of the contemporary theatre. It is not surprising, therefore, that she would self-consciously choose Shakespeare as the model against which to work “Mansfield Park”, the first completed of her second trilogy of novels. Shakespeare was both part of her own education and part of the accepted lore of English culture, he just coming into his Romantic stature as a god-like figure who could even serve as the basis for a set of imitations and reflections in a number of genres for a number of Romantic figures that included Coleridge, Hazlitt, Lamb, and Landor.

Austen says as much within “Mansfield Park”. Jane is playing with her reader when she provides Mr. Crawford, a supposedly obtuse young man, with a speech about how Shakespeare seeps into every Englishman's sensibility, whether the plays are read or not. Fanny and Edmund, who think themselves well read, are horrified at this excuse for ignorance, but they are not prepared to see its truth, which is that there is such a thing as a culture, with its own way of seeing things, that goes beyond a set of quotations or plot summaries. What Crawford says strikes home because it is so candid an admission of how Shakespeare functions even for those who are not particularly literate. By this point in the novel, Jane's readers should know that admissions about how the world serves self interest are usually true observations. Culture operates even upon those who simply wish to appropriate it so that they will seem cultured. So Jane's clue that her own novel is Shakespearean even if it does not again overtly refer to Shakespeare is so obvious that, like the purloined letter, it is likely to be missed.

The structure of “Mansfield Park” is that of a Shakespearean tragedy. First, the plot adds on additional complexities until it becomes a Gordian knot somewhere in the third act. This is the moment of highest emotional distress and tragic recognition. The play then unravels its complexities into some kind of resolution. If the play had been a comedy or romance, there would have been a restoration of family through intricate pairings of lovers on every level of class and generation. If the play is a tragedy, however, the family whose life the play chronicles is destroyed once and for all. Lear's soul is destroyed, but the life of his favorite daughter is also taken. The crown does not descend from Hamlet to some relative but is usurped by Fortinbras. No descendants are mentioned for Anthony and Othello. None of these tragic heroes become connected to future generations. For Shakespeare, tragedy is when a family line ends, because the usual melodrama of fate can no longer operate, as it inevitably does, to merely alter a family or cause it grief. In a tragedy, there is no longer a stable universe of the family within which grief can be acknowledged and overcome.

The same can be said of “Mansfield Park”, which is also about the continuation of families into the next generation, and which ends only with the creation of a replacement family for the Bertrams, rather than any of the marriages that would have simply extended the family line into another generation of gentility built on inherited wealth and community standing. This tragedy is shown indirectly, however, because it does not arise out of a decline in family fortunes, which is the early clue Jane Austen plants to provide suspense about the future of the family, or even with the melodramatic foolishness of some of the characters, who seem to bring the family to ruin because they throw their lives away by loving the wrong people, which is a false trail Jane Austen provides towards the end of the novel and which takes in most readers and critics.

The reader trained on the Brontes is likely to think that Fanny's story is that of an observer who has been brought into the drama to do that and to some extent rescue the fall of the Bertrams. But Fanny is more than an observer; she is a deus ex machina. The story is constructed around Fanny's rise to prominence in the family, which is not just an ironic counterpoint to the fate of the family, but also suggests her growing role in creating that fate. She is the one who appears to come to fit into the world of the Bertrams, but who, in fact, is so unassimilable that her presence skews the responses of others, like the Crawfords, to the Bertrams, and makes more difficult a sensible response by one or another of the Bertrams to the opportunities that avail themselves. Though not the single force that leads to the degeneration of the Bertrams to a family whose best marriage, finally, is between Edmund, a clergyman, and Fanny, his poor relation, Fanny does live up to the prophecy of the Cassandra of the story, Mrs. Norris, who thought from the beginning that Fanny would detract rather than add to the family.

The drama is arranged as a rags to riches story. Fanny's rise in the family from a minor to a major figure accompanies the first part of the drama, which moves from childhood to the crisis of courtship and arrives at its apex when Sir Thomas Bertram returns from Antigua and proceeds to set things on their topsy turvy course--or else to preside over trying to set right what has already gone so amiss that it proves beyond repair. The denouement, suitable for Shakespeare, is full of action as well as attempts to find as right a pairing as is possible that will preserve the future of the family. Sir Thomas is moved to discard one pairing after another, each one of lessened importance, until the final matching of Edmund and Fanny, far from a triumph, comes out as the best that can be done under the circumstances, no matter that it is a love match or that Sir Thomas actually likes Fanny.

Even that minor saving grace is accomplished only after even this last match has been made almost impossible. Fanny has been sent off to Portsmouth, where she had begun her life, with no expectation of a future role in the family drama in which she played so large a role despite herself. The drama is turned full circle: she had arrived at Mansfield Park, found a place for herself there, moved to center stage, then moved herself off center when she refuses to marry Crawford, and then even farther off stage to Portsmouth from which she is rescued only by her usefulness in patching up as best can be events that had gone beyond all control.

This symmetrical movement, which also appeals to Keats and Emily Bronte, runs counter to another feature of the narrative. The pace of the novel picks up as it moves along, and there is an unfolding of ever more sophisticated levels of description by the author, and a building to a final epiphany that changes all meanings, rather than just a central meaning to which the plot ascends and from which it descends.

As in Shakespeare, the stages of plot are symmetrical but the stages of language are successive. In each of the great tragedies, language proceeds from its "lower" to its "higher" forms. Macbeth, Othello, Lear especially, and even Hamlet, move from the language of politics in the first sections of each play, where the characters are concerned with the calculation and balancing of the interests of the political players, a type of language Shakespeare had perfected in “Julius Caesar”, to the language of the great soliloquies, in which the central characters consider the confrontation of mankind with the forces of nature, including the elemental passions. Lear on the heath, Macbeth transformed by his guilt and his understanding of his own nature and nation, Othello confronted with the possibility of his own jealousy, an uncontrollable force which surprises a man whose passions had previously been so in concert with his social position, the protagonist now agonized into eloquence, and so speaking poetry.

Poetry then gives way in the resolution of each of the tragedies to what might be called, following Lear, the language of the birds, the music which allows perfect communication of love and the kind of serenity provided by the survival of tragedy and the appreciation of tragedy. This is very short for Othello, who turns his grief into a ritualistic killing of the one he loves, a sacrifice to the gods performed by him, perhaps for the first time, as an act from which his consciousness is removed. For Macbeth, this period is somewhat more extended, as he resolves to be what he has become, and move ever deeper into blood.

The removal from one language to the next brings a quickening of the pace of the narrative in each tragedy because each level of language operates at its own speed. Events in the political world seem to move quickly only because there is so much talk and analysis of what people mean by each action they take. There are so many implications in any possible action that any action once taken seems a surprise, an intrusion on the never satisfied pace of deliberations. Any action is taken too soon for the significance of the last prior action to have been properly analyzed, and so there is certainly insufficient time left over for the contemplation of an impending event. Politics moves too quickly in real time to allow time for its analysis, and so seems always rushed.

Here is a passage from the first third of “Mansfield Park” which speaks the language of calculation, the prose of political discourse:

“The time was now come when Sir Thomas expected his sister-in-law to claim her share in their niece, the change in Mrs. Norris’s situation,and the improvement in Fanny’s age, seeming not merely to do away any former objection to their living together, but even to give it the most decided eligibility; and as his own circumstances were rendered less fair than heretofore, by some recent losses on his West India Estate, in addition to his eldest son’s extravagance, it became not undesirable to himself to be relieved from the expense of her support, and the obligation of her future provision. “

The language of poetry, for its part, can go on indefinitely exploring the meaning of nature for a new level of insight. Nature comes to mean whatever is eternal because it means what repays infinite contemplation. Nature is not rushed, nor is the plenitude of poetry that it stimulates, but there is no completion of that relationship, because it is timeless, and is altered only when the metaphysical and natural landscape which sparks the poetry is eliminated. Lear could have stayed on the heath forever, or at least only until he died, just as Hamlet could have wondered around Elsinore, forever contemplating the psychological dynamics of kinship and love, if he had not been moved by his thoughts to actions that had consequences. To alter the environment is to take away the object of contemplation, the seat of reverberations.

Now here is a passage from the second third of “Mansfield Park”. It speaks the language of poetry, which is, for Jane Austen, the description of the natural social situation, and is particularly well put by Edmund, Fanny’s true love:

“ “But, Fanny,” he presently added, “in order to have a comfortable walk, something more is necessary than merely pacing the gravel together. You must talk to me. I know you have something on your mind. I know what you are thinking of. You cannot suppose me uninformed. Am I to hear of it from everybody but Fanny herself?” “

These few lines are funny. They are also poetic in the conventional sense because “pacing the gravel together is such an apt image of a walk without conversation. It is also a reflection on the nature of conversation as that is put at a distance from the present occasion to which this wisdom applies. Staying silent when there is something on your mind means that others can reveal it and that is not a good thing if the two parties to the conversation are to consider themselves intimate friends. Edmund’s remarks also indicate that he is someone worthy of Fanny because of his wit and intelligence.

The final language of music is the most quickly paced because action is unhurried since action and language move at the same pace, the language now a direct expression of action, fully integrated with action. Characters, like Lear, need speak very little, and Hamlet can become terse, for actions seem decisive, decisions quickly made, events unfolding with a will of their own as the protagonists adopt the Shakespearean understanding of Stoicism: they appreciate that their own engagement in the world is part of the action of the world rather than merely a cause or a contemplation of actions in the world. They thereby succeed, for a moment, in achieving a kind of simultaneous distance from and acceptance of action.

The characteristics of Shakespearean tragedy hold true for “Mansfield Park”, except that the novel is set in the framework of Humean empiricism rather than the framework of Elizabethan Stoicism. The language of the novel moves from a way to cloak self-interest as good will, which is the way Mrs. Norris talks when Fanny first arrives, and which places Fanny as the outsider who must parse the language to find who are her friends and enemies, where her self-interest lies in the politics of Mansfield Park. The language then shifts, as Fanny becomes a member of the family, to a way to align self-interest with sentiment, which is the way Fanny and the other members of the Bertram family come to talk between themselves as they contemplate the eternal round of life that country life imagines itself to be, full of platitudinous and universal moral truths about the way life has to be, how reality is connected to illusion, and language to sentiments, and how each of us pine to find a way out of the metaphysical impasse of convention and self.

The language of the novel makes a second transition to being a language which is able to speak truthfully and therefore of the consequences of the events described, in which case words are meaningful and, far from being fluff, are all too accurate and lacerating. This new language allows the narrative to move along at ever greater speed, since events can be so quickly telescoped and their implications communicated, if the reader has learned his lessons, and been prepared by Jane Austen's instruction on how to read language and character. The novel can now move into the pace of actual life, rather than operate on the levels of, first, calculation and then, second, the obfuscation or poetry by which we make life managable or, at the least, commensurable.

And here is a passage from the last third of “Mansfield Park”. It speaks the language of the birds, which in this case means the rapid fire emotionally charged action where the events and the meaning are smoothlessly tied together, the events proceeding so rapidly that the characters have little time to consider what is being said but must get on with drawing conclusions. This passage takes place when Fanny has returned to Portsmouth:

”Mr. Crawford contrived a minute’s privacy for telling Fanny that his only business in Portsmouth was to see her, that he had come down for a couple of days on her account and her’s only, and because he could not endure a longer total separation. She was sorry, really sorry; and yet, in spite of this and the two or three other things she wished he had not said, she thought him altogether improved since she had seen him; he was much more gentle, obliging, and attentive to other people’s feelings than he had ever been at Mansfield;....”

Fanny makes instant and complicated judgments of which she feels very sure because that is what is now required by the circumstances but also by the author. Those rapid fire decisions, with which Jane's characters too often seem to indulge themselves, require considerable patience and insight by the reader if they are to be unravelled, even if it is the case that most of life does indeed go on at this pace and does seem to require what might anachronistically be described as simultaneous translation. The consequence of having to cope with subtleties is that life seems to go on much more slowly than it really does. Jane Austen seems to suggest that by careful instruction the reader can be liberated to follow the action quickly by apprehending language as if it were direct, rather than cope with the more realistic slow pace of language that, however accurate, makes the commission of literature so much harder. Literature is artificial because it makes language more accurate and more subtle and more effectual than it really is so that reality can be represented, as in Shakespeare, through eloquence and poetry as well as a music of words that can break through from feeling to action.

The End of "Hamlet"

In Shakespeare’s major tragedies, there are two kinds of movements. The stages of a plot are symmetrical in that an initial situation, such as Hamlet coming home to the wedding of his mother so soon after the death of his father, is complicated by developments that reach some kind of climax in Act III, and then what follows is the unraveling of those events, which usually means that a person who has risen high, such as a Hamlet welcomed home with much pomp, is brought low, thought a madman, before he is done in because he is now disposable, in a duel arranged for that purpose. The same thing happens to Macbeth, who is amazed at his good fortune until he comes to bear the weight of his deeds and so sees a ghost and so drives forward to what he must know is his inevitable fate. Anthony arrives in Egypt as king of the world and ends as the tool of the queen.

Read MoreThe Activity of Conversation

When I was a child and went to visit relatives with my parents, I thought how fortunate I was to be a child because I could go off to play in the room of my relative’s child, and use his toys as well as the ones I had brought with me, while the adults spent their time in the living room just talking. I was not aware of the activity of conversation and what were its rewards. That had to wait until I was slightly older when I would sit on the stoop outside my apartment building and go over what my friends and I had seen on television or what we knew about girls. It is worth pondering conversation as an essential human activity and how it is structured. I will leave to others, such as Roland Wulbert, the question of how we are able to exchange utterances so that they add up to something meaningful.

Read MoreUniversal Roles

Writers and social scientists have always given thought to the sequence of roles that dominate a person’s life and putatively apply to any and all people and so constitute “the ages of man”. Good role theorists that most of them are, they each pick out one or more salient circumstances of each stage that may be obvious but also illuminate the psychological dimensions of that stage as well as its overall meaning. Sophocles, in his riddle of the Sphinx, saw only three stages but his characterization is perhaps still the best in that it is the most minimalist: people crawl on all four as babies; walk erect as adults; and use a cane in old age. Physical frailty characterizes both the last and the first of these stages and so makes the Sophoclean sense of life very sad. Shakespeare thought there were seven stages and he characterized them, in his own vivid way, by a circumstance, an emotion, and an activity. Schoolboys head off to school with their satchels; they are unwilling to do so and whine about it; and they go to school anyway. Soldiers curse a lot, are jealous of their reputations and remain brave even while “in the cannon’s mouth”. All seven stages are portrayed in the most benign way and that suggests that Jacques is speaking in the mood of Arden rather than with the malevolence that Shakespeare usually ascribes to the human condition. That means that one should presume an expositor of universal human roles is not to be trusted, even the present author, whose descriptions are underlain with a sense of the isolation of each human being from other human beings. Erik Erikson, who saw there to be eight stages of psychosocial development, based his view on the basic Christian virtues of faith, hope and charity. He thought that the fundamental stage of human life was the first one, when an infant sensed that he could trust the outside world to be stable and reliable. Basic trust is a form of faith. But Erikson’s idea is also based on a deep insight into what are the circumstances a baby has to manage from the baby’s point of view: the problems of nourishment and comfort. A later stage in Erikson’s schema concerns the ability to engage in a meaningful conjugal relationship, which means having to develop a capacity for intimacy rather than isolation and that challenge is certainly a version of charity. A yet later stage, that of generativity, concerns how a person can take advantage of opportunities to do productive work during one’s adult years, and that is a version of hope.

Read More